Galaxies at the beginning of time invisible due to cosmic air pollution

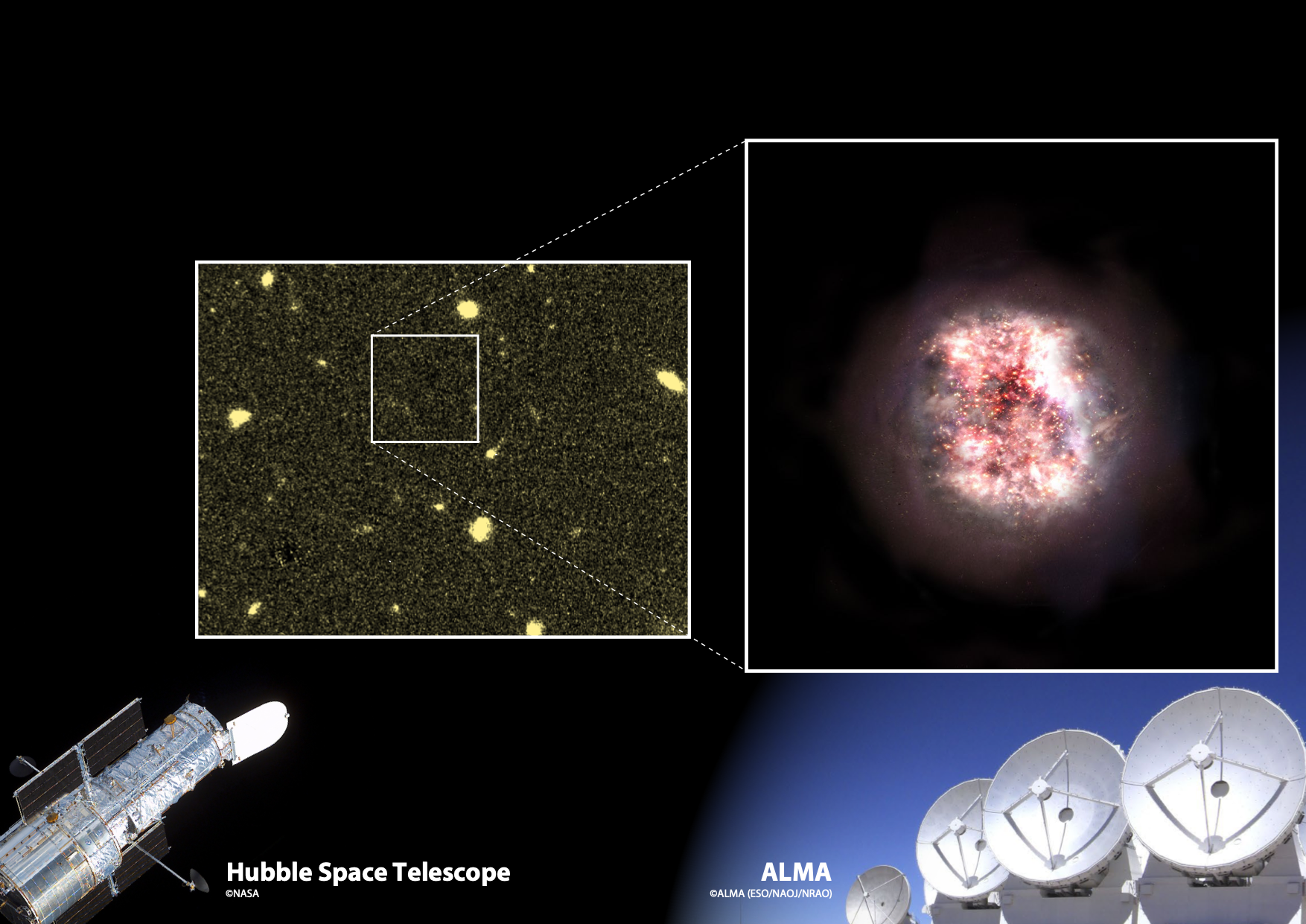

In a sensitive image taken by the Hubble Space Telescope (left) a region of space looks completely empty. Instead, ALMA has now revealed a previously hidden galaxy as it was buried deep in clouds of gas and dust. An artist’s impression of the galaxy is shown on the right. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope.

In summary

- Scientists have found two completely hidden galaxies that formed when the Universe was only in its infancy

- This discovery suggests that many more galaxies might still be hidden and our picture of the beginning of the Universe is far from complete

- The results were published in the journal Nature

While investigating young, extremely distant galaxies through the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) telescope in Chile, astronomers noticed unexpected emissions coming from seemingly empty regions in space.

A global research collaboration that includes two core team members from Swinburne University of Technology discovered that the radiation was emitted billions of years ago and came from two previously invisible galaxies that were hidden by giant clouds of cosmic gas and dust.

This discovery suggests that many more galaxies might still be hidden and our picture of the beginning of the Universe is far from complete.

The results were published in the journal Nature.

When astronomers peer deep into the night sky, they observe what the Universe looked like a long time ago. Light travels at a cosmic snail’s pace, which means by the time it reaches us images of the most distant observable galaxies can paint a picture of the state of the Universe billions of years into the past.

‘Studying these early times, when the Universe was very young and galaxies had just started to form stars, is one of the ultimate frontiers in astronomy,’ says co-author of the study, Swinburne’s Dr Themiya Nanayakkara.

‘It is essential for our understanding of the formation of all stars and galaxies and ultimately tells the story of our own origins.’

In a research collaboration called REBELS (Reionisation-Era Bright Emission Line Survey), astronomers are using the unique capabilities of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) telescope to study distant galaxies at wavelengths of roughly a millimetre.

What the team wants to measure is how fast young galaxies grow by forming new stars. The REBELS team observed 40 distant galaxies at a time when the Universe was only in its infancy – 750 million years old, or five per cent of its current age.

While analysing two of the galaxies, the astronomers noticed a strong mysterious emission at millimetre wavelengths far away from the intended targets. To their surprise, the extremely sensitive Hubble Space Telescope, which probes the sky at shorter visible wavelengths, could not see anything at these locations.

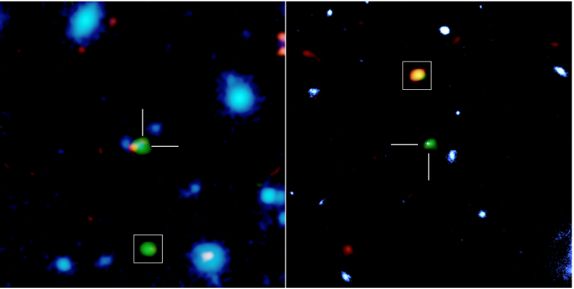

Ultra-distant galaxies as seen with ALMA, the Hubble Space Telescope, and the European Southern Observatory’s VISTA telescope. The two galaxies in the cross hairs were the intended targets. The two galaxies in the squares are surprise detections. Green represents emission from giant dust clouds, orange is radiation from ionised carbon atoms in the clouds (both observed with ALMA) and blue is light from stars seen at near infrared wavelengths with VISTA and the Hubble Space Telescope. The newly discovered galaxies are only seen with ALMA, which suggests that the stars in these galaxies are deeply buried in dust and hidden from view. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, ESO, Fudamoto et al.

To understand the rogue signals, REBELS researchers investigated matters further. Detailed analysis of the signals showed that these were in fact separate galaxies bursting with stars that had been completely overlooked.

Lead author Dr Fudamoto (Waseda University and the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan) explains: ‘These new galaxies were missed not because they are extremely rare, but only because they are completely dust-obscured.’

ALMA was able to solve the puzzle because at millimeter wavelengths it can directly detect the emission of dust and carbon atoms in the gas surrounding the galaxies. One of the galaxies represents the most distant dust-obscured galaxy discovered on record. What is surprising about this inadvertent finding is that the newly discovered galaxies, seen 13 billion years ago, are very similar to galaxies known to exist at later times.

Co-author, Swinburne’s Professor Ivo Labbé says to find such dust-enshrouded galaxies this early in time, less than 1 billion years after the Big Bang, was completely unexpected.

‘Cosmic soot is produced in stars that act as factories,’ Professor Labbé says. ‘It’s a kind of cosmic air pollution, really. Over time you eventually can’t see the stars anymore due to the thick smog.’

The results raise immediate questions about how many more galaxies may be missing.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) – to be launched in December 2021 – will help address these questions. The unprecedented capability of JWST and its strong synergy with ALMA are expected to significantly advance our understanding of the known Universe in the coming years.

‘Completing our census of early galaxies with the currently missing dust-obscured galaxies, like the ones we found this time, will be one of the main objectives of JWST and ALMA surveys in the near future,’ says co-author Professor Pascal Oesch from the University of Geneva.

Swinburne researchers have also been using their access to uniquely powerful WM Keck telescopes in Hawaii to study the chemical properties and black holes of galaxies in the REBELS program.

This study represents an important step in uncovering the true nature and history of the early Universe, which in turn will help us understand where we are standing today.

-

Media Enquiries

Related articles

-

- Astronomy

- Technology

- Health

- Science

- University

- Sustainability

- Engineering

Swinburne highly cited researchers reach the top in 12 fields

Ten Swinburne academics have been named on the Highly Cited Researchers 2025 list, released by Clarivate

Tuesday 02 December 2025 -

- Astronomy

- Technology

- Science

- Engineering

Meet Swinburne’s Roo-ver Mission team

Roo-ver will be Australia's first lunar rover, and it’s being designed, built and tested in Australia. Swinburne is playing a key role in the design and construction of Roo-ver, through its involvement in the ELO2 Consortium.

Wednesday 26 November 2025 -

- Astronomy

- Technology

- Science

- Aviation

- Engineering

Shaping space innovation at the International Astronautical Congress

The 76th International Astronautical Congress (IAC) united over 7,000 delegates from more than 90 countries to explore the future of space. Swinburne staff and students delivered 20 talks, panels and presentations, showcasing Australia’s growing leadership in research and education.

Friday 10 October 2025 -

- Astronomy

Indigenous students explore the cosmos through Swinburne’s astrophysics program

Indigenous students explored astrophysics at Swinburne, connecting science and culture while building pathways to future careers in STEM.

Friday 19 September 2025 -

- Astronomy

- Science

Swinburne’s space stars on show at Parliament House

Swinburne University of Technology hosted a three-day exhibition at Queens Hall in Victoria’s Parliament House . The showcase highlighted the innovative work being done at Swinburne to support the burgeoning space science sector.

Friday 30 May 2025