New stars create space pollution, research confirms

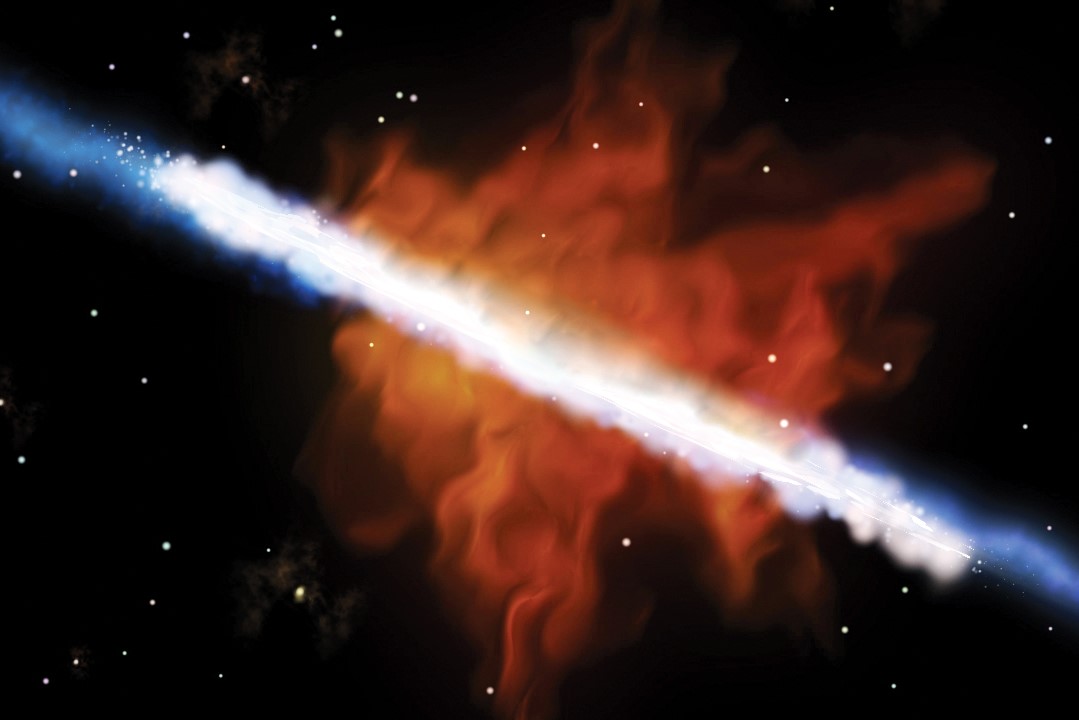

The team lead by Swinburne and Oxford researchers have made the first ever observations of the entire process of new stars polluting the universe around it, confirming a major prediction of galaxy theory. Image credit: James Josephides at Swinburne Astronomy Productions

In summary

- New research confirms that newly-created stars pollute the cosmos, releasing huge amounts of material back into the universe

- To make the discovery, a team of astronomers led by Swinburne’s Associate Professor Deanne Fisher used new imaging technology to study a galaxy 500 light years away

- Swinburne is the only Australian university with access to the WM Keck Observatory in Hawaii, which was used to make the discovery

Swinburne researchers studying a galaxy 500 light years away have revealed how newly-created stars pollute the cosmos.

A team of astronomers, co-led by Associate Professor Deanne Fisher at the Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing at Swinburne University and the University of Oxford’s Dr Alex Cameron, has used a new imaging system at the WM Keck Observatory in Hawaii to confirm that what flows into a galaxy in the process of star-creation is a lot cleaner that what flows out.

Until now, the composition of the inward and outward flows into galaxies could only be guessed at.

This research by the ARC Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D) is the first time the full cycle has been confirmed in a galaxy other than the Milky Way.

“Enormous clouds of gas are pulled into galaxies and used in the process of making stars,” says Professor Fisher.

“On its way in it is made of hydrogen and helium. By using a new piece of equipment called the Keck Cosmic Web Imager, we were able to confirm that stars made from this fresh gas eventually drive a huge amount of material back out of the system, mainly through supernovas.

“But this stuff is no longer nice and clean – it contains lots of other elements, including oxygen, carbon and iron.”

Observing future galaxies

Swinburne is the only Australian university with guaranteed access to the world's largest and most productive optical/infra-red telescopes — the twin Keck Observatory telescopes located near the summit of Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

To make their findings, the researchers focused on a galaxy called Mrk 1486, which lies about 500 light years from the Sun and is going through a period of very rapid star formation.

The elements that were found in the expulsions – known as “outflows” – comprise over half the Periodic Table and are forged deep inside the cores of the stars through nuclear fusion.

When the stars collapse or go nova the results are catapulted into the Universe. Here they form part of the matrix from which newer stars, planets, asteroids and, in at least one instance, life emerges.

Mrk 1486 was the perfect candidate for observation because it lies “edge-on” to Earth, meaning that the outflowing gas could be easily viewed, and its composition measured.

“This work is important for astronomers because for the first time we’ve been able to put limits on the forces that strongly influence how galaxies make stars,” says Professor Fisher.

“It takes us one step closer to understanding how and why galaxies look the way they do – and how long they will last.”

The research is published in The Astrophysical Journal.

Other scientists contributing to the work are based at the University of Texas at Austin, the University of Maryland at College Park and the University of California at San Diego – all in the US – plus the Universidad de Concepcion in Chile.

-

Media Enquiries

Related articles

-

- Astronomy

- Technology

- Health

- Science

- University

- Sustainability

- Engineering

Swinburne highly cited researchers reach the top in 12 fields

Ten Swinburne academics have been named on the Highly Cited Researchers 2025 list, released by Clarivate

Tuesday 02 December 2025 -

- Astronomy

- Technology

- Science

- Engineering

Meet Swinburne’s Roo-ver Mission team

Roo-ver will be Australia's first lunar rover, and it’s being designed, built and tested in Australia. Swinburne is playing a key role in the design and construction of Roo-ver, through its involvement in the ELO2 Consortium.

Wednesday 26 November 2025 -

- Astronomy

- Technology

- Science

- Aviation

- Engineering

Shaping space innovation at the International Astronautical Congress

The 76th International Astronautical Congress (IAC) united over 7,000 delegates from more than 90 countries to explore the future of space. Swinburne staff and students delivered 20 talks, panels and presentations, showcasing Australia’s growing leadership in research and education.

Friday 10 October 2025 -

- Astronomy

Indigenous students explore the cosmos through Swinburne’s astrophysics program

Indigenous students explored astrophysics at Swinburne, connecting science and culture while building pathways to future careers in STEM.

Friday 19 September 2025 -

- Astronomy

- Science

Swinburne’s space stars on show at Parliament House

Swinburne University of Technology hosted a three-day exhibition at Queens Hall in Victoria’s Parliament House . The showcase highlighted the innovative work being done at Swinburne to support the burgeoning space science sector.

Friday 30 May 2025