Breaking down barriers: standing on the shoulders of Australia’s early female chemists

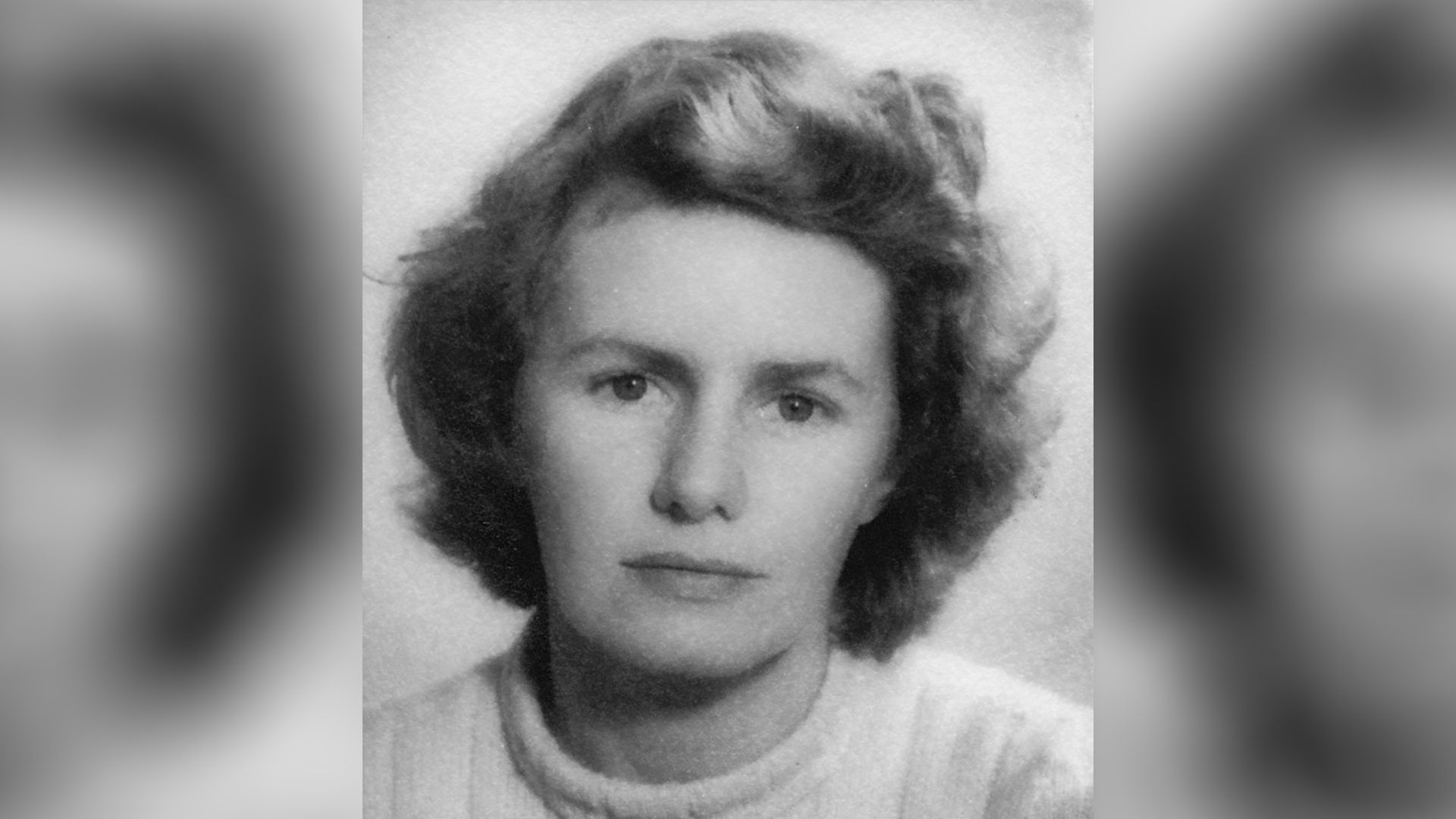

Dr Joy Bear was actively discouraged her from pursuing a tertiary degree by her father who thought it would be “wasted” on her as a woman.

In summary

- New research by Swinburne University of Technology and Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, highlights the stories of the nation's early female chemists

- Researchers pay tribute to the women's contribution to both science and gender equity

- The experiences of these women highlight the importance of brave individuals in driving legislative and societal change

Expected to resign after marriage and faced with sexist attitudes about their capacity for science, Australia’s early women chemists had a constant fight to remain in the field.

Their incredible stories, often overlooked in mainstream narratives of history and science, have been documented in new research by Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, and Swinburne University of Technology's Professor Thomas Spurling, Gregory Simpson and Helen Wolff.

Breaking down barriers: standing on the shoulders of Australia’s early female chemists, published on Saturday 11 February, to coincide with the United Nations International Day of Women and Girls in Science, shines a light on the experiences of trailblazing Australian chemists Dr Joy Bear (1927–2021), Enid Plante (1918–2007), Catherine Money (1940–), and Professor Annabelle Duncan (1953–).

Enid Plante was Enid Plante was the first woman appointed to the Physical Chemistry Section of CSIR (later CSIRO) in 1940.

Making strides for gender equity

Bear, who among other fellowships and awards is on the Victorian Honour Roll of Women and a Member of the Order of Australia for her services to science, was actively discouraged her from pursuing a tertiary degree by her father who thought it would be “wasted” on her as a woman.

Later, her colleague wrote in a reference letter when she applied for promotion that he, “never thought that women have the same capacity for original thought and particularly what I would call ‘inventive capacity’ compared with men”.

CSIRO researcher Nicole McNamara paid tribute to Bear and her contemporaries for their contribution not only to science, but to gender equity.

“The experiences of these women are not unique to any sector, and many of these sexist attitudes remain pervasive today,” Dr McNamara said.

“But there’s no question about the very real strides made by Joy Bear and other powerful women of her calibre to affect change.

“We owe them a great deal of thanks for that.”

Catherine Money a world-leading and award-winning chemist, responsible for many improvements in the leather treatment industry.

Remembered and celebrated

Money came into the workforce the same year the ‘marriage bar’ (legislation preventing married women from working) was abolished, and with attitudes shifting she was able to negotiate support from her husband and managers at CSIRO to achieve the flexibility to continue working after marrying and having children.

She went on to become a world-leading and award-winning chemist, responsible for many improvements in the leather treatment industry, including game-changing leather preservation methods that facilitated sustainable processing of hides.

Swinburne researcher Helen Wolff said Money’s experience highlighted the importance of brave individuals in driving legislative and societal change.

“Let’s not pretend we live in a perfect world today, because women still face so many barriers to equality,” Ms Wolff said.

“But Catherine Money and others have earned their place in history for the barriers they knocked down.

“They deserve to be remembered and celebrated, and that’s why our research and these stories are so important.”

Microbiologist Annabelle Duncan was the first female scientist in the chemistry-based division at CSIRO.

-

Media Enquiries

Related articles

-

- Design

- Technology

- Health

- Law

- Education

- Business

- Science

- University

- Engineering

Swinburne moves up in Times Higher Education World University Rankings by Subject 2026

Swinburne University of Technology has performed strongly in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings by Subject 2026, with two subjects moving up the ranks.

Thursday 22 January 2026 -

- Technology

- Science

- University

- Aviation

- Sustainability

- Engineering

Swinburne secures AEA funding in aerospace, critical metals, sustainable steel production and protective helmet design

Swinburne University of Technology researchers have secured over $1.6 million in funding from Australia’s Economic Accelerator (AEA) Ignite grants.

Thursday 22 January 2026 -

- Student News

- Science

- Sustainability

Introducing tomorrow’s global science communicators

Start Talking is Swinburne’s unique video-based public speaking competition, exclusively for undergraduate students

Monday 08 December 2025