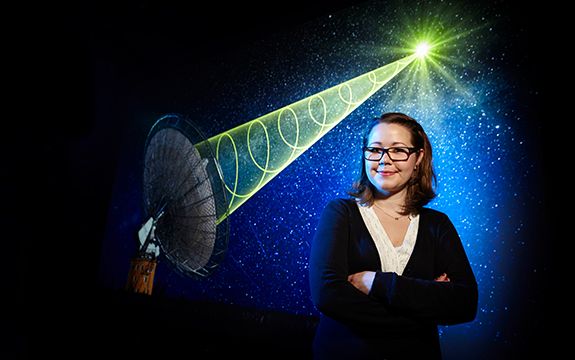

Dr Emily Petroff

Swinburne stories | Trailblazers

Swinburne PhD graduate and astrophysicist

As a young girl growing up in Oregon in the United States, Emily Petroff was inspired by documentaries about space and the work of American astronomers Carl Sagan, astrophysicist Neil de Grasse Tyson and British cosmologist Stephen Hawking. Her parents bought her a telescope when she was eight and Emily dreamed of becoming an astronaut. But after watching the movie Apollo 13 at the age of 12 (‘Houston, we have a problem’) she decided astronomy was the safer option.

Now aged just 27, an astrophysicist and a postdoctoral researcher working in the Netherlands, Emily’s career trajectory since she completed her PhD at Swinburne in 2015 has been meteoric. Emily gained international media attention earlier that year as part of a team at Swinburne’s Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing that discovered perytons — strange new signals first believed to be lightning, solar bursts or transient events from within the Earth’s atmosphere — were caused by the office microwave. Although the media made sport of the story, Emily says the discovery of the perytons had important implications for future research.

Dr Emily Petroff

Discovering real-time fast radio bursts

In 2014, while using Australia’s famous Parkes Observatory radio telescope, known from its movie fame The Dish, the team more significantly discovered fast radio bursts (powerful bursts of light) believed to be coming from outside the galaxy. Emily was monitoring activity at The Dish in central New South Wales when the signals were recorded and she notified astronomers from across the globe about the discovery. ‘We felt really confident that we had actually found a burst in real time,’ she says.

Theories about what caused the burst, believed to have come from a galaxy over five billion light years away, include a neutron star, an energetic flare from a star, or a star collapsing into a black hole. Emily says she hopes the bursts are something ‘we have never thought of before’.

"Some of the exciting discoveries I made with my team, including the first real-time fast radio burst discovery, really seemed to capture the public imagination..."

Emily conducted as much outreach and public engagement as possible to generate interest in the discoveries Swinburne was leading. She wrote articles for The Conversation website and appeared in a short television documentary screened on SBS. She regularly gave talks about her work and discoveries to visiting groups of alumni and to others within the university, as well as giving a public lecture near the completion of her PhD. ‘Through all of this I was learning valuable skills in research (the most important thing in a PhD) but also in communication, which has served me incredibly well,’ she says.

‘Some of the exciting discoveries I made with my team, including the first real-time fast radio burst discovery, really seemed to capture the public imagination and teach people about this exciting new mystery source that we are still trying to understand.’

In January 2016 Emily moved overseas to work in a postdoctoral research position at the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON), continuing her work on fast radio bursts and pulsars. ‘In astronomy, it’s pretty typical to do a postdoctoral position or two after you complete your PhD to focus on research and advance through academia,’ she says. ‘I'm starting that journey and really enjoying my time in the Netherlands.’

At the Netherlands institute Emily is working to upgrade the Westerbork Synthesis Radio Telescope. ‘We are putting brand-new technology in the telescope to make it faster and more sensitive. When it’s up and running it will be one of the premier fast radio burst finders in the world,’ she says.

A strong research education

Emily has fond memories of starting her PhD work at Swinburne in August 2012. ‘I chose Swinburne because the research group lead by Professor Matthew Bailes was doing incredibly interesting and innovative research and I wanted to be a part of it,’ she says. ‘From the moment I arrived I was learning all these new things from talks and seminars within the Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, but at the same time learning so many new things about my new research projects from my supervisors and research group. The Hawthorn campus was really lively and energetic and I enjoyed my work right from the beginning,’ she says.

"I chose Swinburne because the research group lead by Professor Matthew Bailes was doing incredibly interesting and innovative research and I wanted to be a part of it."

Swinburne provided a strong research education and Emily says the university offered opportunities to communicate her work to broader audiences. ‘I competed in and won the Swinburne 3-Minute Thesis competition in 2015 and got to represent the university at the Trans-Tasman Final that year, which was a really great experience,’ she says.

Emily nominates her PhD supervisors as early mentors. ‘They didn't teach me everything I know, but they came pretty close,’ she says. Her coordinating supervisor for her PhD was Dr Willem van Straten and her secondary supervisor was Professor Matthew Bailes. ‘Both were so patient with me as I learned the ropes and explored my new research environment,’ she says. ‘I had so many questions and they were there to answer (or try to answer) almost every one of them. I'm endlessly grateful to them and they both inspired me all the time through their expertise and their excellent supervision.’

Emily says she was inspired by the strong women at the centre who were advocating for women in astronomy. ‘The Australian astronomy community has some very strong voices on gender issues and some of the strongest are researchers at Swinburne,’ she says. She names the university’s Professor Sarah Maddison, Professor Virginia Kilborn and Associate Professor Emma Ryan-Weber as inspirations in the centre and for encouraging Emily to join its Equity and Diversity committee. ‘It ended up being one of the most rewarding non-academic activities of my PhD life,’ she says.

"The Australian astronomy community has some very strong voices on gender issues and some of the strongest are researchers at Swinburne."

'When I started my PhD I thought I was going to work on these stars called pulsars that live in our galaxy and have been a field of study for almost 50 years,’ she says. ‘But right when I started there was interest in fast radio bursts and I started to investigate them as part of my own research. This led me on an entirely different track but it was full of exciting discoveries, solving mysteries and getting to be at the forefront of a rapidly growing new field in astronomy.’

Maintaining a connection with Swinburne

Emily’s work in the Netherlands maintains her connections with Swinburne. ‘I work with research groups around the world on scientific papers and results, including the group at Swinburne,’ she says. ‘I still work with Matthew Bailes and his research group on some of the projects I began during my time at Swinburne and I hope to come back and visit soon.’

She remembers with affection a daily ritual at Swinburne’s Hawthorn campus. ‘Every morning at 10 we would go down to the cafe on the ground floor of our building and have coffee together, talk about our work, the material from recent talks we’d had in the centre, or really anything,’ she says. ‘I still really miss that time.’

The universe continues to surprise

Australia remains at the forefront of work in the field of fast radio bursts partly through Emily’s discoveries and she has been invited to present her work at conferences across the world for a wide range of astronomy audiences.

She is unsure about her next career move. ‘I suppose I will have to see where my research takes me but I would like to continue working in research and with research students for as long as I can,’ she says. ‘I hope that my work has given people a glimpse of the crazy world of astronomy and some of the cool things we're starting to find. This new class of objects that we’re starting to learn about is teaching us that the universe still has some surprises in store.

Words by Peter Wilmoth.

Keep on exploring

-

Swinburne stories

-

Collaboration and partnerships

-

Alumni

-

Giving to Swinburne