Billionaires’ space race could help our planet

Earth, dubbed the “Blue Marble”, as seen by the Apollo 17 crew in 1972. This image resonated with people worldwide.

In summary

Opinion piece for The Age by Professor Alan Duffy, Director of the Space Technology and Industry Institute at Swinburne University of Technology

It’s easy to be cynical about the future of the planet as our billionaires launch themselves and their companies into space, but I – for one – have hope. We know from the early days of space flight, with former military test pilots as the first astronauts, the experience of seeing Earth from space has a near universally profound impact on a person. Space philosopher and author Frank White coined the term the overview effect to describe it.

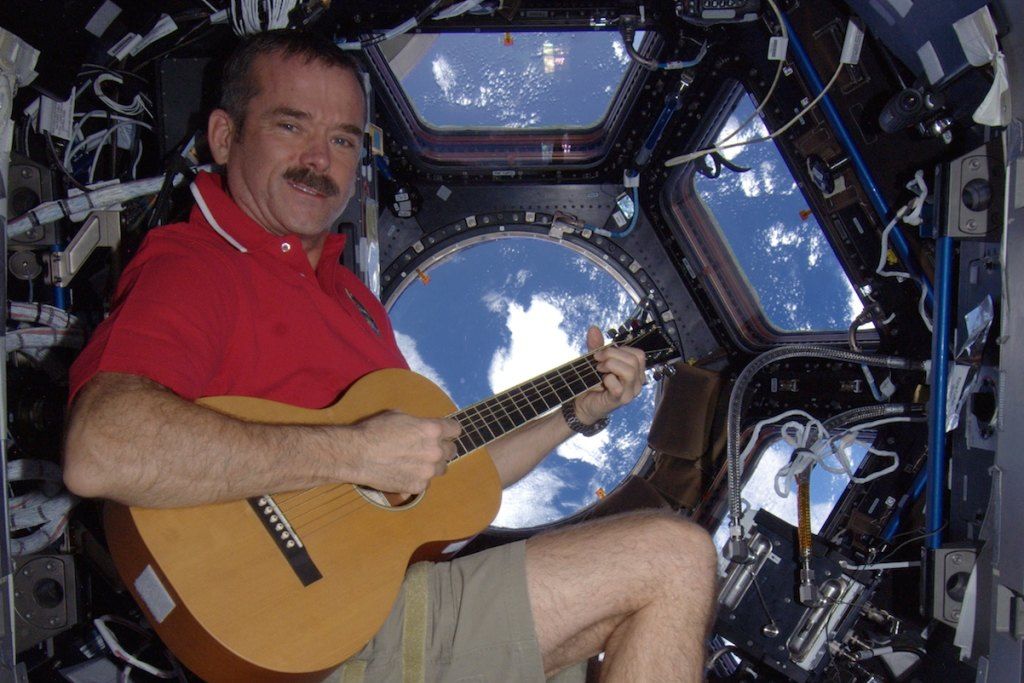

Astronauts and cosmonauts report space flight as a lasting, transformative experience, and we’ve seen many of them become active in environmental causes as a result. People like first cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, Michael Collins of Apollo 11 and, more recently, Sally Ride, Chris Hadfield and Anne McClain have all spoken of this perspective shift.

It’s no coincidence that the environmental movement globally grew in strength, scale and significance when we saw Earth suspended in the void of space. The iconic “Blue Marble” seen by the Apollo 17 crew in 1972 resonated with people worldwide as a transformative reminder of the reality of our existence. There is a thin veneer of atmosphere around the ball of dirt where all our lives are led and lived, and we need to look after it better.

What happens when our wealthy see a fragile Earth? The world’s wealthiest people will be the first space tourists, but they will also experience first-hand the overview effect. With their money, power, and influence, we can only imagine how they could change the planet for the better if they are moved in the way that former military pilots have been.

Passengers of SpaceX and, it is planned, Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos’ company, will have a true, orbital experience of space – taking potentially month-long or days-long trips around the Earth, out to the International Space Station or even lapping the moon. On these trips, they’ll see the Earth surrounded by a sea of blackness.

Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson are in a race to take wealthy tourists into space. Credit: AP

Space tourists taking a sub-orbital parabolic flight as Sir Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic did this monthwill skim just short of the Karman line – the 100-kilometre official international designation of space, although fortunately for Sir Richard his astronaut wings are recognised by NASA, which states 80 kilometres as the boundary.

All up, these passengers experience a few minutes of microgravity as the craft falls back to Earth, experiencing that fall as weightlessness. Earth will occupy most of the view, with the blackness of space just above – not far removed from what Gagarin described on the first human flight in space.

As we see hundreds, if not thousands, of people become space tourists, we could also see an empowered group of the world’s wealthy back on Earth motivated to do more to protect it. Democratising space can only be a good thing. Space tourism today is an experiment. It could be a billion-dollar market, but we don’t yet know for sure how many people will pay for (and can afford) this unique, once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Luckily my hope for the potential positives of space tourism doesn’t just rely on the number of people we get into space and the cognitive shift they might experience. Growth in tourist launches will also drive the scale and sophistication of rockets, making overall access to space more affordable, just as early pioneering travellers allowed the aviation industry to grow and become more technologically advanced, ultimately driving costs down.

Astronaut Chris Hadfield has talked about his improved understanding of threats facing the planet since seeing Earth from space.

At Swinburne University of Technology’s Space Technology and Industry Institute, we already benefit from the effects of space tourism with our Swinburne Youth Space Innovation Challenge where we send up students’ scientific experiments to the International Space Station. This kind of educational experience would be inconceivable without the commercial rockets that have now become so relatively accessible.

Yet, it remains the case that only the richest countries and companies get to reach space and benefit directly. As access becomes more affordable, we can see all countries and people benefit – as well as the planet.

The possibilities are extraordinary. Satellite information can be used to improve agricultural yields to tackle world hunger, or to facilitate fast and efficient disaster relief and emergency services, or to allow us to monitor the health of the planet and inform climate solutions. Indeed, these benefits are intimately tied to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. All 17 goals rely directly or indirectly on space and satellite technology.

One of the major barriers to satellite technology being used to tackle the world’s greatest challenges is cost, and therefore access. With space tourism driving down costs, that barrier is being eroded – and that gives me real reason to hope for the future of this blue marble in space.

Professor Alan Duffy is an astronomer and Director of the Space Technology and Industry Institute at Swinburne and lead scientist of the Royal Institution of Australia.

This article was republished with permission from The Age. Read the original article.

-

Media Enquiries

Related articles

-

- Technology

- University

World-first partnership with Adobe drives tech-fluency at Swinburne

Swinburne has become the first Adobe Creative Campus in the world to provide all staff and learners with Adobe Creative Cloud, including Adobe’s full offering of generative AI tools

Tuesday 27 January 2026 -

- Design

- Technology

- Health

- Law

- Education

- Business

- Science

- University

- Engineering

Swinburne moves up in Times Higher Education World University Rankings by Subject 2026

Swinburne University of Technology has performed strongly in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings by Subject 2026, with two subjects moving up the ranks.

Thursday 22 January 2026 -

- Health

Revealing the parental role in preventing childhood internet addiction and how to combat it

New Swinburne-led research has found that the use of mobile devices by primary school-aged children for gaming, social media and streaming significantly increases the risk of internet addiction – and parents are the main influence.

Tuesday 20 January 2026 -

- Technology

- Science

- University

- Aviation

- Sustainability

- Engineering

Swinburne secures AEA funding in aerospace, critical metals, sustainable steel production and protective helmet design

Swinburne University of Technology researchers have secured over $1.6 million in funding from Australia’s Economic Accelerator (AEA) Ignite grants.

Thursday 22 January 2026 -

- Technology

Swinburne-led network to guide AI use in youth services

Swinburne’s Dr Joel McGregor, Dr Linus Tan and Dr Caleb Lloyd have established the Responsible AI in Youth Sectors Network. The collaborative network aims to guide the fast-growing use of artificial intelligence in youth services across Victoria.

Friday 12 December 2025