Brave John Kerr judgment followed letter of law

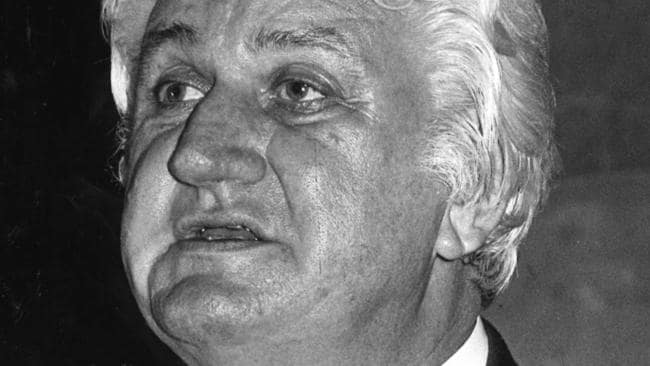

There has been intense political debate for more than four decades about whether the dismissal of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam in 1975 was appropriate or constitutional, says Dean of Swinburne Law School, Professor Mirko Bagaric.

In summary

- Opinion piece for The Australian written by Dean of Swinburne Law School, Professor Mirko Bagaric

It took 45 five years for palace letters relating to the Dismissal of the Whitlam government to be released, but they will do nothing to quell the intense debate that lasts to this day regarding the greatest political and constitutional crisis in our history.

There has been intense historical, legal and political analysis for more than four decades regarding whether it was appropriate for governor-general Sir John Kerr to dismiss prime minister Gough Whitlam on November 11, 1975.

It is a debate unlikely to be settled because while it is clear that under Australia’s constitutional system the governor-general can dismiss a prime minister, the circumstances and process pursuant to which this power can be exercised are not clearly articulated.

Instead, the authority to dismiss a prime minister is found in the unwritten reserve powers of the crown.

One circumstance where dismissal power can be exercised is if a government cannot secure supply. And it was on these grounds that Kerr invoked those powers when he so eloquently and succinctly explained his decision to remove the Whitlam government: “Because of the federal nature of our Constitution and because of its provisions, the Senate undoubtedly has constitutional power to refuse or defer supply to the government. Because of the principles of responsible government, a prime minister who cannot obtain supply, including money for carrying on the ordinary services of government, must either advise a general election or resign.”

Debate rages about whether Kerr should have given Whitlam more time to try to secure supply.

The palace letters provide no further meaningful insight into the appropriateness of Kerr’s action, but do give a deep insight into the manner in which the decision was made.

Kerr expressly acknowledges the importance of the decision to potentially dismiss a duly elected prime minister and it is obvious the significance of that decision was not lost on him. Much will be made of the fact he chose not to inform the Queen ahead of his decision to dismiss Whitlam. However, it is vital we do not overstate the importance of this decision.

There is no rule (written or otherwise) requiring a governor-general to seek the approval of or to inform the Queen of actions that would involve dismissing a prime minister. It is clear that this power rests with the governor-general. Moreover, before the Dismissal, Kerr did expressly confirm with the Queen’s private secretary, Sir Martin Charteris, that he had the power and authority to dismiss the Whitlam government.

The decision to not notify the Queen before the sacking was a judgment call by a person who was prepared to take full accountability for his decision and who wanted to distance the monarch from unnecessary involvement in a political controversy. The prudence of this judgment call will be debated for many decades.

What is less debatable is the robustness, stability and success of our constitutional monarchy system of government.

The Queen, as head of the Commonwealth (who delegates her powers to the governor-general), is the final arbiter concerning how intractable political impasses are to be resolved.

A decision by a (non-elected) monarch to sack a serving prime minister is a drastic step in any governmental system. In many societies, lesser forms of political intervention have led to violent internal conflict.

Not so in our system of government. While Whitlam was sacked by an unelected official, the process that was then triggered was wholly democratic. And at this forum the people cast their vote on the desirability of the Dismissal.

This article was republished with permission from The Australian. Read the original article.

-

Media Enquiries

Related articles

-

- Student News

- Law

Students tour South Korea’s evolving legal landscape

Swinburne University of Technology’s law students recently undertook a two-week study tour to South Korea, focused on legal affairs, political systems and local customs. The group of 14 students, led by Dr Jacqueline Meredith, took part in an immersive educational experience designed to deepen their understanding of international legal systems.

Thursday 07 August 2025 -

- Law

Top Law Student Awarded Supreme Court Prize

Swinburne graduate, Zachary Plant, was presented with the Supreme Court Prize by Chief Justice Richard Niall and Federal Court Chief Justice Mortimer for academic excellence, as Swinburne’s top Law student for 2024.

Monday 14 July 2025 -

- Law

Students develop tech solution for major Melbourne law firm

Swinburne Law students have created an innovative triage tool to streamline Australian Consumer Law assessments for major consumer products law firm, CIE Legal.

Monday 14 July 2025 -

- Law

Academic discovery and cultural exchange during Vietnam tour

Students made lifelong connections and gained international industry insights on the first Law, Governance and Culture study tour to Vietnam.

Tuesday 20 August 2024 -

- Law

Swinburne law academic wins Victorian Premier’s History Award

Associate Professor Amanda Scardamaglia has won this year’s award for writing the first book that documents the visual history of print advertising in Australia.

Thursday 29 October 2020