Curious Kids: why do we think there is a possible Planet X?

Image: Shutterstock

In summary

Analysis for The Conversation by Dr Sara Webb from the Centre of Astrophysics and Supercomputing

Why do we think there is a possible planet X? – Courtney, Year 5, Victoria

Hi Courtney, what a great question!

Our Solar System is a pretty busy place. There are millions of objects moving around – everything from planets, to moons, to comets and asteroids. And each year we’re discovering more and more objects (usually small asteroids or speedy comets) that call the Solar System home.

Astronomers had found all eight of the main planets by 1846. But that doesn’t stop us from looking for more. In the past 100 years we’ve found smaller distant bodies we call dwarf planets, which is what we now classify Pluto as.

The discovery of some of these dwarf planets has given us reason to believe something else might be lurking in the outskirts of the Solar System.

Could there be a ninth planet?

There’s a good reason astronomers spend many hundreds of hours trying to locate a ninth planet, or “Planet X”. And that’s because the Solar System as we know it doesn’t really make sense without it.

Every object in our Solar System orbits around the Sun. Some move fast and some slow, but all move abiding by the laws of gravity. Everything with mass has gravity, including you and me. The heavier something is, the more gravity it has.

A planet’s gravity is so large it impacts how things move around it. That’s what we call its “gravitational pull”. Earth’s gravitational pull is what keeps everything on the ground.

Also, our Sun has the largest gravitational pull of any object in the Solar System, and this is basically why the planets orbit around it.

It’s through our understanding of gravitational pull that we get our biggest clue for a possible Planet X.

Unexpected behaviours

When we look at really distant objects, such as dwarf planets beyond Pluto, we find their orbits are a little unexpected. They move on very large elliptical (oval-shaped) orbits, are grouped together, and exist on an incline compared to the rest of the Solar System.

When astronomers use a computer to model what gravitational forces are needed for these objects to move like this, they find that a planet at least ten times the mass of Earth would have been required to cause this.

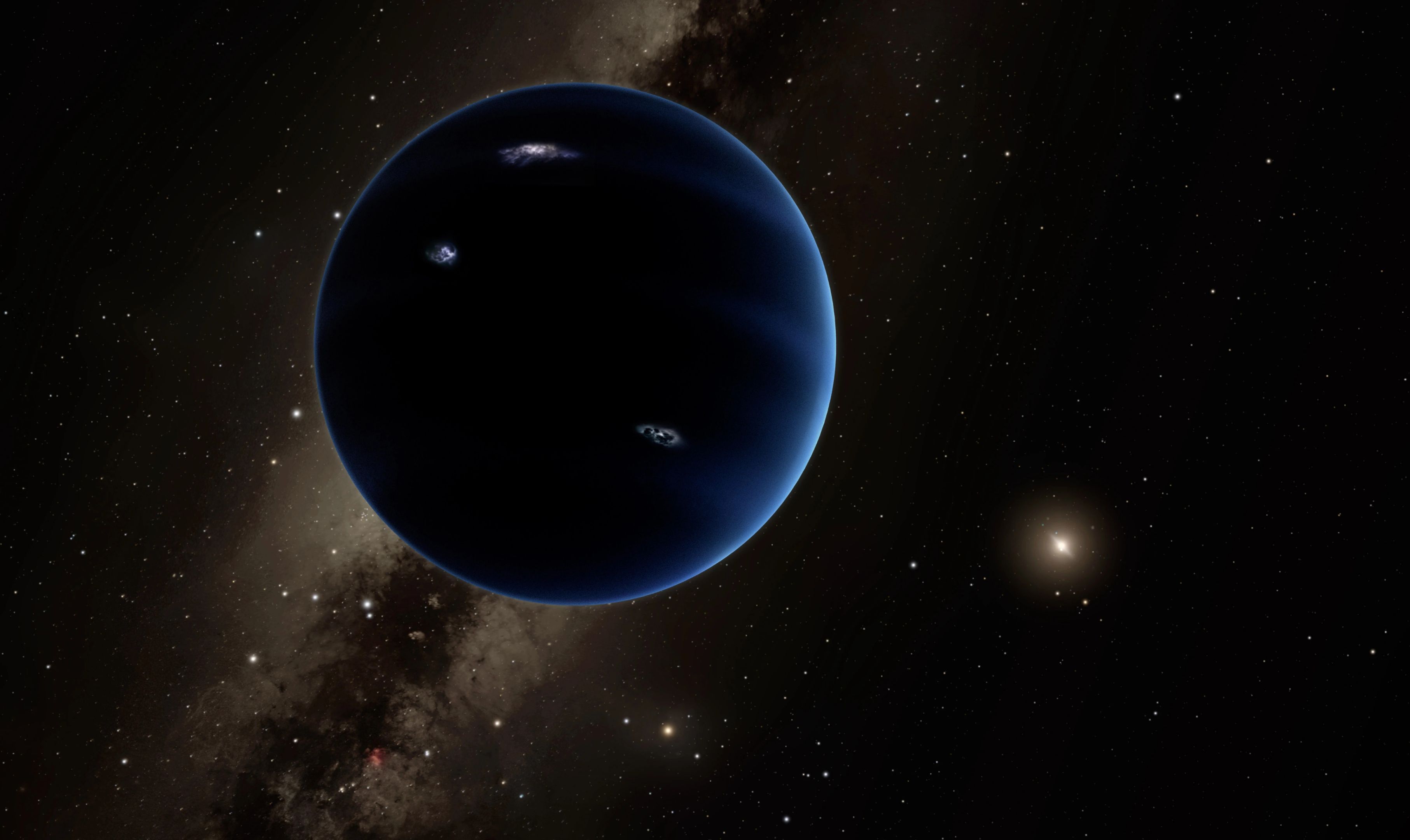

If Planet X is real, it’s probably a gas giant like Neptune. Image: NASA/Caltech/R. Hurt (IPAC), CC BY

It is super-exciting stuff! But then the question is: where is this planet?

The problem we have now is trying to confirm if these predictions and models are correct. The only way to do that is to find Planet X, which is definitely easier said than done.

The hunt continues

Scientists all over the world have been on the hunt for visible evidence of Planet X for many years now.

Based on the computer models, we think Planet X is at least 20 times farther away from the Sun than Neptune. We try to detect it by looking for sunlight it can reflect – just like how the Moon shines from reflected sunlight at night.

However, because Planet X sits so far away from the Sun, we expect it to be very faint and difficult to spot for even the best telescopes on Earth. Also, we can’t just look for it at any time of the year.

We only have small windows of nights where the conditions must be just right. Specifically, we have to wait for a night with no Moon, and on which the location we’re observing from is facing the right part of the sky.

But don’t give up hope just yet. In the next decade new telescopes will be built and new surveys of the sky will begin. They might just give us the opportunity to prove or disprove whether Planet X exists.

Astronomers explain their reason for thinking there is a ninth planet. Credit: California Institute of Technology.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

-

Media Enquiries

Related articles

-

- Astronomy

High school students work with Swinburne astronomers on the future of space

Swinburne’s Youth Space Innovation Challenge has inspired over 330 Australian teenagers to pursue a career in STEM.

Friday 26 July 2024 -

- Astronomy

- Science

Swinburne appoints new Director of Innovative Planet Research Institute

Leading geodesy expert, Professor Allison Kealy, has been appointed as the inaugural Director of Swinburne University's Innovative Planet Research Institute.

Monday 22 April 2024 -

- Astronomy

- University

OzGrav 2.0: A ‘new era of astrophysics’ launched at Swinburne

The next phase in the world-leading ARC Centre of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Discovery, dubbed 'OzGrav 2.0', launched this week at Swinburne University of Technology.

Wednesday 17 April 2024 -

- Design

- Astronomy

- Technology

- University

Swinburne ‘Rock Muncher’ takes part in Australian Rover Challenge

A multidisciplinary student team from Swinburne University of Technology competed in the 2024 Australian Rover Challenge held in Adelaide, South Australia.

Thursday 11 April 2024 -

.jpeg/_jcr_content/renditions/cq5dam.web.256.144.jpeg)

- Astronomy

New JWST observations reveal black holes rapidly shut off star formation in massive galaxies

New research showcases new observations from the James Webb Space Telescope that suggest black holes rapidly shut off star-formation in massive galaxies by explosively removing large amounts of gas...

Tuesday 23 April 2024