The Moral Machine: Navigating the ethical rules of autonomous vehicles

In Summary

- Deputy Director and Program Leader (Future Urban Mobility) Smart Cities Research Institute, Associate Professor Hussein Dia, comments on the results of a large global study on driverless car ethics

An online experimental platform developed by MIT researchers is helping to explore the moral dilemmas posed by autonomous vehicles. Dubbed the ‘Moral Machine’, the platform was used to collect data on people’s moral preferences about how autonomous vehicles should decide who to spare in situations where accidents are unavoidable.

The results of the experiment are intriguing.

The findings, published this week in Nature, are based on almost 40 million decisions collected from participants across the globe. The massive survey has revealed some distinct global preferences about the ethics of autonomous vehicles, and is also helping to yield valuable public-opinion information to guide the development of socially acceptable AI ethics.

The Moral Machine experiment

The idea of robots making real-time decisions on who should live and who should die may sound far-fetched. But with the rapid pace of developments in AI and machine learning, we could be edging closer to a point in time when robots may need to make that ‘moral’ call.

When autonomous vehicles become a reality, they will need to navigate not only the road, but also the moral dilemmas posed by unavoidable accidents. Ethical rules will need to guide their AI systems in these situations. And if self-driving vehicles are to be embraced, we need to determine in advance which ethical rules the public will consider acceptable.

To address this challenge, the researchers created the online experimental platform to explore people’s preferences. They gathered decisions from millions of people in 233 countries around the world. The respondents were presented with a series of situations where the vehicle must act, and were asked to choose between two outcomes and decide who is spared and who is sacrificed.

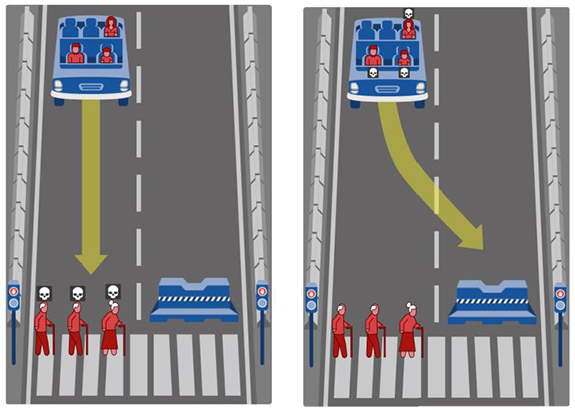

The platform was used to generate data and insights on how these vehicles are likely to distribute the harm which they cannot eliminate in case of unavoidable accidents. For example, if an autonomous vehicle experiences a system failure and a crash is imminent (see below), should it stay on course and kill two elderly men and an elderly woman (left), or swerve into a wall and kill the three passengers: an adult man, an adult woman, and a child (right).

Moral Machine presents users with increasingly complex moral questions. Credit: Scalable Cooperation, MIT Media Lab.

Moral Machine presents users with increasingly complex moral questions. Credit: Scalable Cooperation, MIT Media Lab.

The experiments focused on nine factors: sparing humans (versus pets), staying on course (versus swerving), sparing passengers (versus pedestrians), sparing more lives (versus fewer lives), sparing women (versus men), sparing the young (versus the elderly), sparing pedestrians who cross legally (versus jaywalking), sparing the physically fit (versus the less fit), and sparing those with higher social status (versus lower social status).

The Findings

The research findings provide fascinating insights into the societal expectations about the ethical principles of autonomous vehicle behaviour. They also improve our understanding of how these preferences are likely to contribute to developing socially acceptable principles for machine ethics.

There was a strong preferences for sparing humans over animals, sparing more lives, and sparing young lives. While these preferences appear to be essential building blocks for machine ethics, the researchers found they were not compatible with the first and only attempt to provide official guidelines on machine ethics, as proposed in 2017 by the German Ethics Commission on Automated and Connected Driving.

For example, they found that the German rules do not take a clear stance on whether and when autonomous vehicles should be programmed to sacrifice the few to spare the many. The same German rules state that any distinction based on personal features, such as age, should be prohibited. This clearly clashes with the strong preference for sparing the young (such as children) that was assessed through the Moral Machine.

Another interesting aspect of this research is the cultural clustering of results, where the analysis identified three distinct ‘moral clusters’ of countries that each share common ethical preferences for how autonomous vehicles should behave. These are: Western cluster including North America and Europe; Eastern cluster including far eastern countries such as Japan and Taiwan; and a Southern cluster including Latin American countries.

The analysis showed that ethics diverged hugely with some striking peculiarities. For example, there was a less pronounced preference to spare younger people in the Eastern cluster; a much weaker preference for sparing humans over pets in the Southern cluster; a stronger preference for sparing higher status people in the Eastern cluster; and a stronger preference for saving women and fit people in the Southern cluster.

The findings come with caveats, of course. The respondents in this survey were entirely self-selected and the data is likely to be skewed towards the tech-savvy. These are also ‘stated preferences’ – people’s revealed preferences may be very different when real lives are at stake.

The Implications

The design and regulation of autonomous vehicles could potentially vary by country.

While these results demonstrate the challenges of developing universally acceptable ethical principles for autonomous vehicles, the real value of this work will be in starting a global conversation about how we want these vehicles to make ethical decisions.

Regardless of how rare these unavoidable accidents will be, the ethics principles surrounding autonomous vehicles should not be dictated based on commercial interests.

We, the public, need to agree beforehand how these should be addressed, and convey our societal preferences to the companies that will design the moral algorithms, and to the policymakers who will regulate them.

Associate Professor Hussein Dia is Deputy Director and Program Leader (Future Urban Mobility) Smart Cities Research Institute.

Learn more about the program led by Associate Professor Dia that is creating safe and resilient urban transport and mobility solutions.