Transparency can work both ways

In Summary

Opinion piece for The Australian by Professor Mirko Bagaric, Dean of Law, Swinburne University of Technology

Australians dislike government secrecy but some yearn for even more privacy. We can’t have it both ways. The so-called “right to privacy” logically and morally underpins secrecy, whether it relates to activities by individuals or governments. It is hypocritical for activists to demand greater transparency by government while agitating for an express legal right to privacy.

The recent Right to Know campaign highlighted the decline in government transparency and accountability and the erosion that this is causing to the democratic process. Government secrecy is so pervasive that only 37 per cent of us believe we are adequately informed about government activity. Governments keep secret a wide range of important decisions they make, including in the areas of tax assessment, property ownership, surveillance, health and aged care.

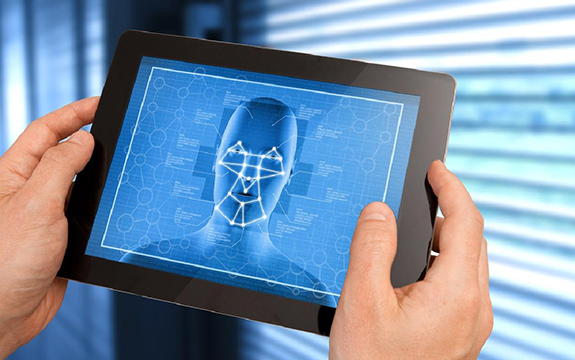

The reality is that the flourishing of society is being compromised not only by government secrecy but also by the broader pursuit of privacy. For example, we would benefit significantly should the day come when facial recognition cameras that detect suspicious human activity are installed in every street and public area.

Research suggests that this will go a long way to eliminating crime in public places and would spare thousands of Australians the trauma of being a victim of an assault, rape, robbery or worse.

The most likely reasons for the drop in crime in the US during the past 20 years is the mobile phone, which is used as an (albeit crude) evidence-gathering and crime-detection device.

Building a technology system that detect and gathers evidence regarding crime will go a long way to eradicating it in locations that are monitored. And it has no downside.

Some commentators have misguided concerns over the use of facial recognition cameras. Facial recognition is not yet perfect, but the error rate is much lower than human identification. The single most common cause of wrongful conviction in our legal system is wrong identification stemming from the frailties of human recognition and memory.

Computers are profoundly more accurate than us at identifying people. Moreover, if a person wants to challenge a computerised identification there is always a record of that image. With humans we are too often dealing with the distorted memory of a fast-moving event.

The community also should welcome increased monitoring of the computer activities of each individual. The only people who have something to fear from their computer keystrokes and searches being monitored, collated and examined are those who are engaging in illegal behaviour.

Every few months, we read of a substantial “data breach” where the details of users of a computer platform are exposed, or we are informed of systematic monitoring of our computer activities by entities such as Google and Facebook or perhaps security officials. But the sum tangible damage caused by these billions of breaches is zero. The reality is that the Cambridge Analytica data harvesting “scandal”, for example, did not result in a single individual being harmed.

If you are doing nothing wrong, the worst that will happen to you if Google, the Australian Federal Police or Australian Taxation Office collate every keystroke you have ever entered on your computer is that you will receive more advertising and newsfeeds that align with your interests – hardly an ant sting.

On the plus side, the community will be profoundly better off because thousands of terrorists, pedophiles and tax dodgers will be detected and hopefully prosecuted.

The activist rallying cry that we are going to be harmed if government departments or Google or Apple acquire more information about us is a myth. Governments, advertisers and marketers have been profiling individuals for decades. These days they just do it more effectively.

Previously we were profiled by information such as our age, race, job, postcode and income, and now added to that are our movements (through tracking of our mobile phones, CCTV surveillance and travel passes) and our search history. Nothing has changed apart from the accuracy with which we are profiled.

This can’t harm us. It would be a bad business model for governments or sellers to use such information to damage the community. Moreover, it is illegal. The benefit of living in a democracy is that individuals can influence governments and police (often with the assistance of the media) to enforce the law.

There are legitimate boundaries of privacy, but they start and end with security concerns. People are entitled to keep confidential their bank account details and prevent others entering their property and peering through their curtains, but anything beyond that is a reflexive quest for individualism at the expense of the society-enhancing sharing of information.

It is not surprising that the communities that are most harmonious and where people are happiest are country areas where people know far more about each other and interact more frequently than urban areas where mass human congestion has the perverse effect of people leading more isolated existences.

If people still want to insist on greater individual privacy to guard against such nebulous interests as their reputation, commercial concerns and to prevent information from getting into the “wrong” hands they will need to accept ongoing and increasing government secrecy. The reality is that the same type of interests that privacy advocates invoke to agitate for greater privacy are the identical interests that governments use in a bid to justify secrecy. If people want a transparent government, they need to accept a more transparent society.

Mirko Bagaric is Dean of Law at Swinburne University of Technology and the author of Privacy Law in Australia.. This opinion piece was originally published in The Australian.