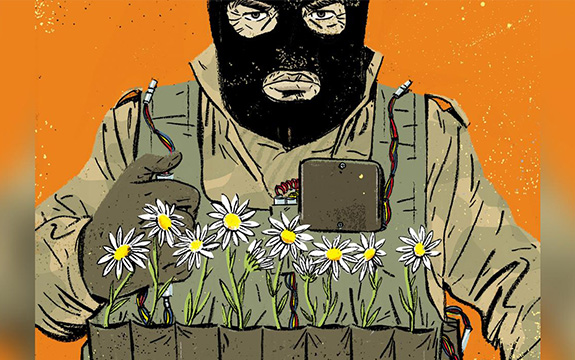

Opinion: Here’s why we must not trust ‘reformed’ terrorists

In Summary

- Opinion piece for The Australian by Professor Mirko Bagaric, Dean of Law, Swinburne University of Technology

Sentencing has several objectives, but when it comes to terrorism offences only one aim is appropriate: community protection. Compromising this objective for any other goal, such as rehabilitation, is breathtakingly misguided.

It is for this reason the federal government should introduce a mandatory 30-year prison term for any adult convicted of a terrorism offence that involves killing or the attempted killing of another person.

The latest London Bridge attack in which convicted terrorist Usman Khan killed two people, has sparked an urgent sentencing review in Britain. In 2013, Khan was convicted of plotting to bomb the London Stock Exchange. Incredibly, he was released late last year under a licence that involved him being subjected to electronic monitoring.

The issue of how to properly sentence terrorists is particularly acute in Australia, given the large number of people we have convicted of serious terrorism offences. More than 40 people have been convicted of terrorist acts here, including three who were sentenced last week for planning to slaughter large numbers of people in Melbourne’s CBD on Christmas Day in 2016. Surprisingly, one man received a minimum term of just 16½ years.

The Commonwealth Criminal Code enables courts to keep terrorist offenders in prison for up to three years after their sentence has expired — more than one order can be made — if courts are satisfied to a high degree of probability that the offender will commit a serious offence if released into the community. The problem with this provision is it places the burden on the prosecution to establish that the offender is likely to reoffend.

There would be no need for provisions of this nature if the sentencing of offenders for serious terrorism offences was appropriate at the outset. In determining the appropriate penalty for such crimes we need to be clear-minded about the nature of terrorism. It involves the deliberate attempt to kill innocent people — typically as many as possible, including children — to advance an ideological cause with the purpose of intimidating the public and influencing government policy.

A defining aspect of terrorism is that the act is never spontaneous. It is always planned and calculating. It aims to destroy human life wantonly, often in barbaric ways. Unlike many other crimes, there is no way for people to reduce their risk of being a victim of a terrorist event.

Pointedly, research data shows that terrorists overwhelmingly do not suffer from mental illness. Their decision deliberately to kill innocents is the most extreme example of rational cognitive disfigurement. These are people who calmly think about their life trajectory and goals, and conclude that it is not only tolerable but also desirable to go about slaughtering innocents for their cause.

Now, there is a broad spectrum of activities that the human mind is capable of believing is acceptable. But at some stage a point is reached where the wiring of some people is simply so strange and dangerous that they lose their right to participate in conventional society. They are simply too bad. Not mad, just off-the-scale bad.

Their belief system is so extreme, it is impossible to have confidence that their attitudes can be modified. They will always live outside the bounds of tolerable behaviour. Anyone capable of killing so calculatedly and randomly to achieve their objectives must be removed from the community.

Of course, there may be some terrorists who, during a long jail stint, come to their senses.

And certainly the criminal justice system should generally prioritise rehabilitation as a sentencing goal. It is in fact one of the best approaches to community protection.

Moreover, offenders generally should be punished commensurate with the seriousness of their crimes. As I have stated on this page before, we should look at greatly reducing prison numbers, perhaps by half. Let’s reserve prison for people who scare us, not those who anger us (such as white-collar offenders, low-level drug offenders and thieves).