Could Congestion Pricing Provide a Panacea for Melbourne’s Gridlock?

In Summary

- By Professor Hussein Dia, Deputy Director, Smart Cities Research Institute, Swinburne University of Technology

- Hussein Dia is Professor of Future Urban Mobility at Swinburne University of Technology. He currently serves as Chair of the Department of Civil and Construction Engineering, and Deputy Director of the Smart Cities Research Institute

- Professor Dia was invited by the Institute of Public Administration Australia to write the article for their website

Anyone who has tried to drive across Melbourne during the morning or afternoon peak hours will know that the world’s second-most liveable city has a major traffic problem.

According to a 2018 study by the Australian Automobile Association, Melbourne’s commuters have seen their speeds drop more than any other Australian city over the past five years. Commuting trips in Melbourne were 2.7 per cent slower in 2018 than in 2013 – compared to a 1.4 per cent decrease in Sydney and Brisbane.

The current construction blitz isn’t expected to provide much relief either. The latest Infrastructure Australia Audit 2019 found the huge pipeline of road and rail projects, both underway and planned, will not prevent Melbourne or Sydney becoming paralysed with congestion by 2031. The cost of congestion in the two cities is expected to double – even when taking into account the expected benefits to flow from $200 billion in road, rail and public transport projects.

Solutions and opportunities

These challenges are not unique to Australian cities. Despite decades of investment in transport infrastructure, many cities around the world face similar challenges. Decision-makers in these cities all agree there is a problem, and have tried a myriad of congestion-busting solutions and policies, with little success.

But our knowledge – and the policy landscape – is finally shifting. There is more recognition today that building additional infrastructure provides little relief from congestion. The benefits from increased network capacity tend to occur only in the short-term and over time are offset by the growth in traffic from induced demand. Gridlocked roads not only impede cars, they also slow down the bus and tram services many cities are pushing hard to promote.

Increasingly, the focus on tackling congestion is shifting to managing demands for travel and determining how best to address them through pricing instruments and signals. In many jurisdictions, congestion charging and road pricing reforms are increasingly seen as an enabler for better management of demand and more efficient use of the road network.

Deeply-rooted conceptions

The idea of charging road users is not new. It has long been argued that roads are valuable assets and scarce resources that should be valued by imposing costs on users. Proponents argue that when governments give away something valuable for free, they create limitless demand for its use. But the concept of ‘putting a price on driving’ has often clashed with our car-loving culture, where people consider driving the ultimate freedom – and roads the ultimate free resource.

Today, because most commuters rarely pay directly for roads, or because the true cost of using them is less visible to drivers, it can seem that they are free for everyone to use. But drivers are already paying for every trip they take — the immediate costs beyond petrol and parking (e.g. insurance, registration and maintenance) are just not as transparent as they are for public transport users. The result is a misconception that driving is cheap – which further encourages people to drive.

The key challenge for policymakers is to counteract the deeply-rooted idea that roads and streets are free. Congestion pricing remains a tough sell for political dealmakers, particularly as it advocates that drivers should pay for something they have long demanded and largely believe they’ve been receiving for free.

But if the momentum for a congestion pricing policy spreads, it will achieve a paradigm shift and a radical change in managing how commuters get around, and even how ridesharing companies like Uber, Ola and Didi operate in our cities.

A movement for change

The idea behind congestion pricing is that when people see that driving costs more, they drive less. This is the most direct policy lever for tackling congestion and the reason why the movement is gaining traction as one of the most effective measures for addressing inner-city congestion.

Singapore, London, Stockholm and Milan all have congestion charging schemes. The benefits reported by these cities are compelling, including substantial reductions in traffic congestion, fewer private vehicles entering restricted zones, increased public transport use, reduced emissions and greater road safety. In addition to saving money and lives, congestion pricing in these cities also raises millions of dollars each year, which are reportedly used for improving public transport, cycling and other active transport amenities.

And the movement is spreading. Earlier this year, New York City approved plans to adopt congestion pricing in Manhattan – paving the way for the rest of the country to seriously consider a policy once thought to be politically toxic. Portland, Philadelphia, Los Angeles and San Francisco are all now considering various forms of pricing.

In Australia, pricing instruments have been paraded for some time as a key approach to fix our transport problems. The Henry Tax Review in 2009, the Productivity Commission review of public infrastructure in 2014 and the Harper Review in 2014 all urged governments to consider road pricing as a matter of priority. These studies also recommended that governments conduct pilot studies to demonstrate the benefits of pricing to road users. In more recent times, Infrastructure Australia, the RACV, Infrastructure Victoria, the Grattan Institute and other peak bodies have also called for its introduction in major cities.

Better than building roads

Throwing money at huge infrastructure projects will eventually meet with limited success. This approach continues today however, and is very popular with governments and political leaders who target the benefits to key voters, while distributing the costs among all taxpayers.

According to the latest Grattan Institute report, sensible and fair congestion pricing could be introduced that targets only busy roads and areas like central business districts during periods of high demand, and avoids burdening the financially disadvantaged who don’t have other options.

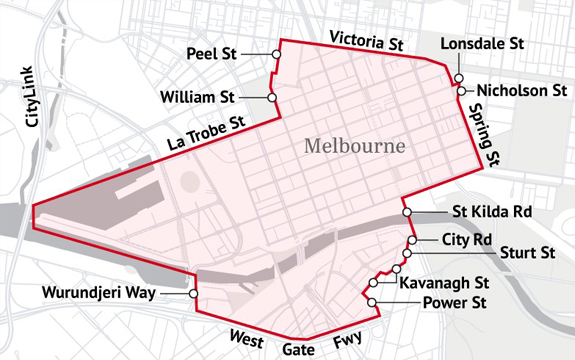

The Grattan report estimates that in Melbourne a cordon-based congesting pricing schemecould see drivers pay $10 a day to travel into and out of Melbourne’s CBD ($5 in the morning peak and $5 in the afternoon) – resulting in the removal of 5,000 cars from roads each day. A $3 charge would apply in the half-hour either side of the morning peak, and in the hour before and the half-hour after the afternoon peak. Driving to and from the CBD would remain free at all other times, and on weekends and public holidays.

An independent economic regulation body such as the Essential Services Commission would ultimately recommend the price of these cordon charges, with revenue (estimated at $124 million per year) collected by the state government. The revenue could be spent on upgrades for pedestrians, improvements to bus routes, and giving buses and trams traffic signal priority.

Example of a cordon-based charging area in Melbourne’s CBD. Source: The Age

Example of a cordon-based charging area in Melbourne’s CBD. Source: The Age

A congestion-free future?

Although the Victorian Government has rejected the Grattan proposal, this unpopular idea is not likely to go away. It will keep resurfacing until cities finally buy into it. This is a powerful policy whose time has come. If it is not adopted as an effective instrument for relieving congestion, the move could eventually come as a response to declining revenues from the federal fuel excise or as an alternative to existing transport taxes. Future options could also include road pricing on a per-kilometre basis during busy periods, or as part of a holistic package of measures to abolish transport taxes while creating a safety net for people on low incomes.

While such reforms remain challenging territory for our policymakers, the climate for change in Australia is likely to become easier as more cities around the world prove that congestion pricing can work fairly and gain public acceptance. This will then give cities like Melbourne and Sydney the impetus they need to start pushing in earnest for a congestion charge.

Hussein Dia is Professor of Future Urban Mobility at Swinburne University of Technology. He currently serves as Chair of the Department of Civil and Construction Engineering, and Deputy Director of the Smart Cities Research Institute.