The impact of landmark images in mobile mapping apps

In Summary

- Designer Andrew Haig investigates the impact of images in mapping apps

- Photographs of landmarks create building blocks of spatial information

- Images assist people travelling to and from unknown destinations

The use of images of landmarks in mobile map applications could make finding your way to and from destinations easier. Andrew Haig, Lecturer in Communication Design at Swinburne, is investigating the impact of landmark images in mobile mapping apps.

His research shows how photographs of landmarks create ‘building blocks’ of spatial information. Seeing landmarks on a map can guide and assist people travelling to and from unknown destinations.

“My research investigated how mobile maps can be improved by including photographs of landmarks in the map interface. Research shows that users of mobile maps, compared to users of paper maps, develop less spatial knowledge of an area for two main reasons,” says Mr Haig.

“Firstly, mobile map route instructions are automated, so a user doesn’t have to plan their route and perform map-related tasks, such as rotating the map to match the environment, or locate themselves on the map. These cognitive tasks help people to understand the environment around them. Secondly, only a small part of a large map is visible on-screen, so a user doesn’t fully understand the context of what they are seeing. This is known as the ‘keyhole problem’,” he says.

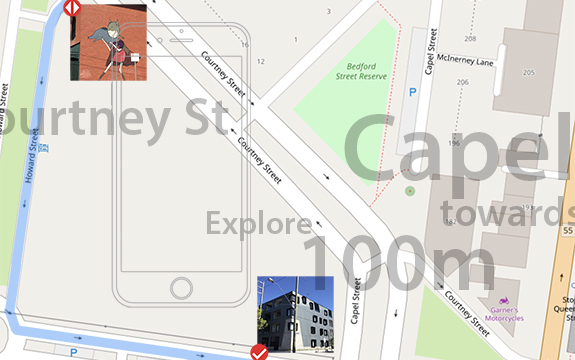

Images and map data, copyright OpenStreetMap contributors

“Theoretical frameworks of spatial knowledge acquisition reveal that landmarks can teach us about spaces. As we travel we look for noticeable, conspicuous things in the environment to guide us and aid our memory of a region. After repeat journeys in a region, we develop survey knowledge - having learnt about landmarks, the routes and paths around them to gain more knowledge of a region. Although some can learn this knowledge much faster than others,” Mr Haig explains.

“I added landmarks to the interface of a mobile maps system, to test if they aided the acquisition of survey knowledge in users. My research revealed that acquired knowledge of an area could be of great assistance – if a mobile device battery or data connection fails on a return visit, or if the GPS signal in an area is weak,” he adds.

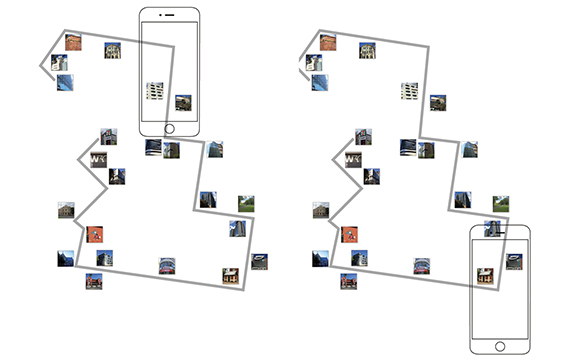

A depiction of the concept: how landmarks found along a route can be used on-screen within mobile maps

Mr Haig devised studies to compare wayfinding with conventional mobile maps using landmarks in various ways. The studies show landmarks are used for following a route and remembering surroundings, so much so that some users are able to take shortcuts back to parts of the route, by remembering the landmarks along it.

“Shortcuts demonstrate that some survey knowledge has been acquired. Users of landmarks in the studies acquired more survey knowledge due to their learning of them,” says Mr Haig.

He plans to expand his research at Swinburne to investigate how landmarks in a mobile map interface can guide non-native speakers and people with learning or language comprehension difficulties.