Brutalism: how to love a concrete beast

In Summary

- Analyis for The Conversation by DJ Huppatz, Associate Professor of Architecture and Design, Swinburne University of Technology

No other architectural style elicits emotional reactions like Brutalism. Think monolithic concrete buildings composed of blunt rectangular forms, devoid of colour, decoration or symbolism, with cavernous interiors that complement the exterior’s hulking, inhuman scale.

Frequently described as dehumanising, depressing and oppressive, Brutalist buildings feature prominently in “world’s ugliest buildings lists”.

Despite this unpopularity, architects, preservationists and historians in Britain, the United States and Australia have embarked on numerous campaigns over the past decade to save Brutalist buildings from demolition.

How could anyone love such concrete beasts?

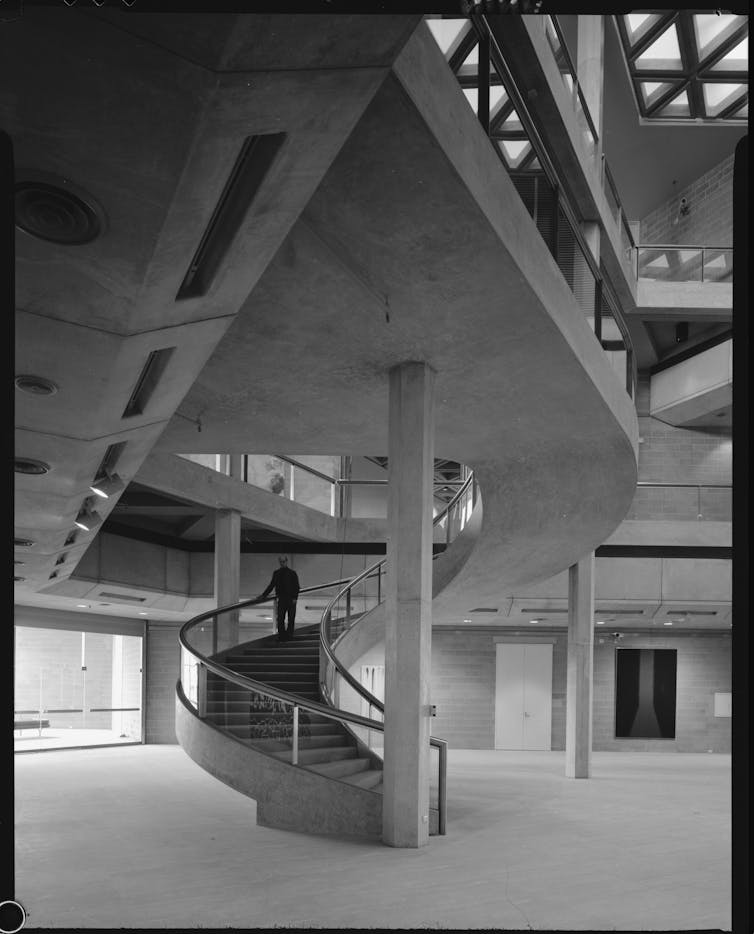

Australia’s High Court: a brutalist classic. Mick Tsikas

Australia’s High Court: a brutalist classic. Mick Tsikas

An honest material

Brutalism sounds intimidating (as in brutal), but its origins lie in a modernist penchant for béton brut (raw concrete). In the 1920s, famed French architect Le Corbusier popularised an architecture comprising simple cubic forms of raw concrete as the epitome of modernism.

Read more: The problem with reinforced concrete

For modernists, concrete was a futuristic material that could fulfil their utopian dreams of mass housing and urban renewal. It was flexible yet solid, malleable yet permanent. Unrefined concrete was an honest expression of their intentions, while plain forms and exposed structures were similarly sincere.

The Palace of Justice, Corbu Chandigarh, India, designed by Le Corbusier. Wikimedia Commons

The Palace of Justice, Corbu Chandigarh, India, designed by Le Corbusier. Wikimedia Commons

And concrete has its own qualities. No two concrete surfaces look or feel the same. Textured with impressions of the wooden form-work or sandblasted to expose its gravel aggregate, concrete walls have a subtle beauty.

But Brutalist buildings (like all buildings) require regular maintenance, and concrete deteriorates. Brown stains leak from joints due to metal reinforcements rusting from within. Public buildings particularly suffer from neglect.

Callam Offices, Woden, ACT. Wikimedia Commons

After the second world war, with the advent of metal reinforcing, concrete came into its own with greater expanses and stronger structures and Brutalism become a global phenomenon. From Soviet Bloc housing complexes to Western European welfare state projects, Brutalism became a modern, efficient and cheap solution for mass public housing.

It also became a favoured style for public institutions, particularly government buildings, cultural complexes, schools, universities and hospitals.

An ethical approach

In a 1957 edition of Architectural Design, architects Alison and Peter Smithson argued that it was more than just a style:

Brutalism tries to face up to a mass-production society, and drag a rough poetry out of the confused and powerful forces which are at work. Up to now Brutalism has been discussed stylistically, whereas its essence is ethical.

The Smithsons’ best-known project and exemplar of British Brutalism was the Robin Hood Gardens, a high-rise public housing scheme in London completed in 1972. Its ethical dimension was a new approach to mass housing with generously-sized flats and two-metre-wide “streets in the air” running the length of the blocks every third floor. (But the flats were neglected for years and demolition of them began in 2017.)

Robin Hood Gardens photographed in 2017 before demolition. Wikimedia Commons

Robin Hood Gardens photographed in 2017 before demolition. Wikimedia Commons

In the 1960s and 1970s, Brutalism became a global style, with few concessions to local climate or conditions and concrete monoliths were built in as diverse places as Singapore and Sao Paolo. Brutalism in the postcolonial world was functional, economical, and it made new nations appear progressive.

In Australia, prominent architect and critic Robin Boyd wrote sympathetically about Brutalism in The Australian Ugliness as it spread here in the 1960s.

Canberra’s High Court Building and National Gallery of Australia, public service buildings such as the Cameron Offices, Sydney’s UTS Tower and Brisbane’s Cultural Precinct are prominent local examples. Perth’s Art Gallery of WA is celebrating its 40th anniversary with the exhibition Perth Brutal: Dreaming in Concrete.

Fritz Kos Art Gallery of Western Australia 1979. Sourced from the collections of the State Library of Western Australia and reproduced with the permission of the Library Board of Western Australia (224276PD)

Fritz Kos Art Gallery of Western Australia 1979. Sourced from the collections of the State Library of Western Australia and reproduced with the permission of the Library Board of Western Australia (224276PD)

Controversy over the fate of Sydney’s Sirius building in the Rocks raised the issue of Brutalist conservation in Australia.

Read more: In praise of the Sirius building, a ruined remnant of idealistic times

Meanwhile, in Victoria, the intimidating Footscray Psychiatric Centre, was quietly recommended for Heritage listing recently by Heritage Victoria. Completed in 1976, this four-storey, windowless concrete block seems an unlikely Heritage contender, but it is certainly an exemplary Brutalist building.

Stuck with beasts

Beyond their architectural function, Brutalist buildings serve other uses. Skateboarders, graffiti artists and parkour practitioners, for example, have all used Brutalism’s concrete surfaces in innovative ways.

Brutalist architecture has also featured regularly in dystopian sci-fi films – from A Clockwork Orange to Blade Runner 2049 – and enthusiasts share moody, black and white photographs on Instagram’s Brut Group and the global activist database SOS Brutalism.

Whether we see Brutalist buildings as concrete monstrosities blighting our cities or heroic, modern sculptures from a pre-digital age is really a question of taste. But it is worth considering Brutalism’s ethics and politics further.

Firstly, Brutalism evokes an era of optimism and belief in the permanence of public institutions – government as well as public housing, educational and health facilities. Secondly, while demolishing Brutalist buildings often proves politically popular, they are typically replaced by private development.

Aesthetics provides a cover for this move, especially in inner cities where Brutalist institutions sit on valuable land. But restoration and renovation, rather than demolition and rebuilding, are often more sustainable solutions.

So before we call for the wrecking ball, we could look again at our concrete beasts. Below that rough skin, we might see a little brutish charm.

Perth Brutal: Dreaming in Concrete will be at the Art Gallery of Western Australia from 21 September 2019 – 3 February 2020.![]()

By DJ Huppatz, Associate Professor of Architecture and Design, Swinburne University of Technology. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.