Most adults have never heard of TikTok. That’s by design

In Summary

- Analysis for The Conversation by Kath Albury, Professor of Media and Communication and Milovan Savic, PhD Candidate, Swinburne University of Technology.

TikTok is one of the fastest growing social media platforms on the planet, with more than 500 million active users. Only YouTube, Facebook and Instagram boast more.

TikTok allows users to create short videos with music, filters and other features. But while it’s now used globally by young people, many adult social media users have never heard of it. That’s by design.

In 2016, we conducted an ethnographic study on social media use among families with preteen children in Melbourne. Although most young participants in the study were considered by their parents to be “too young” for social media, some had accounts on a new platform called Musical.ly – now known as TikTok.

We soon realised that the preteen demographic was central to Musical.ly’s success – and to its evolution. The rapid increase of smartphone ownership among preteens presented a relatively uncaptured potential user base for social media.

Many big players have made recent attempts to capture this particular audience. Snapchat’s SnapKidz, YouTube Kids and most recently Facebook’s Messenger Kids all focused on creating a “child-friendly” version of the main app.

The creators of Musical.ly did their homework. They not only identified potential future users of the app, but also non-users that might hamper their success. In order to reach preteen audiences, social media apps need to get past the gatekeepers of preteen online engagement: the parents.

Read more: TikTok is popular, but Chinese apps still have a lot to learn about global markets

Billing itself as a tool for creativity

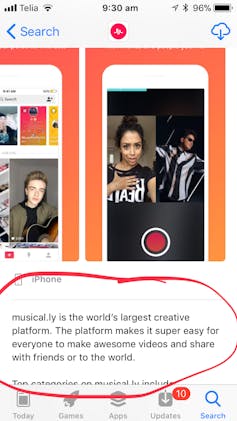

Musical.ly’s description in app stores promoted it as a creative tool rather than a social media platform.

From the beginning, Musical.ly presented itself as a tool for creativity and play rather than a social media platform. This tactic enabled Musical.ly to alleviate parental concerns associated with childrens’ use of social media. The app store description reads: “the world’s largest creative platform.”

Childrens’ engagement with digital devices is often driven by their desire for creative expression, entertainment and social interaction. Musical.ly successfully engineered playfulness and performativity as its key features.

For example, its cleverly coined “best fan forever” feature mimics elements of popular teen culture allowing users to establish a special connection with features like duet videos. “BFFs” individually record their videos of the same song, which the app then combines into a duet. In this way, users are incentivised to spend more time interacting together on the app.

Everything you can do on Instagram

While TikTok still bills itself a “community of global creators”, it’s more than just a toy for children. TikTok allows users to follow and interact with “public” profiles. They can follow each other (reciprocity not required), like and comment on videos, and send direct messages to each other.

In other words, TikTok meets all elements of a social networking site. In fact, the app’s infrastructure largely resembles Instagram.

Read more: How Tencent became the world's most valuable social network firm – with barely any advertising

From Musical.ly to TikTok

The user base is the most valuable asset of any social media platform. During 2016 and 2017, Musical.ly, a social media start-up from China, was trending among most downloaded apps on both Apple and Google’s app stores.

This led to its acquisition by the Chinese media giant ByteDance for US$1 billion. We have seen similar scenarios before, when a successful start-up is acquired by a bigger player on the market.

When it acquired Musical.ly, ByteDance was mostly focused on news and was largely absent from social media landscape. But it did own a short-video sharing platform branded as Douyin. At the time, Douyin was not well known outside of China.

In 2018, ByteDance decided to merge Douyin and Musical.ly under the name TikTok. While the merger brought some new features, the process was virtually undetectable to users, who kept their accounts and all preexisting content and followers.

In other words, overnight the Musical.ly user database became the TikTok user database. While Musical.ly was more popular among global north, TikTok dominated the Asian market, positioning the newly merged app for a wider global audience reach.

Unwanted attention

In its early days TikTok managed to fly under the radar, but its rapid growth and growing user base has brought the app unwanted public scrutiny.

In 2018 the Indonesian government temporarily banned the app amid accusations it was disseminating pornography and blasphemy. In February 2019, India’s High court requested both Google and Apple remove TikTok from Indian app stores following accusations the platform was spreading pornographic and violent content.

Possibly the largest hit came earlier this year when US Federal Trade Commission fined TikTok a record-setting US$5.7 million (A$8.2 million) for collecting and storing the personal information of people under the age of 13 without obtaining parental consent (as required by law).

As TikTok has come to the public’s attention, parents and commentators have increasingly expressed concerns regarding potential predatory behaviour, bullying and exposure to the age-inappropriate content on the app.

Read more: Thinking of taking up WeChat? Here's what you need to know

Challenging US social media dominance

Some may see TikTok as just another social media platform that will soon disappear, but it’s more than that. It’s the first social media platform based in China that commands unparalleled popularity in both Asian and Western markets.

This undermines the dominance of US companies on the global social media market. TikTok’s challenge going forward will be to live up to the promise of networked play and creativity, while ensuring the personal safety and data security of its users.![]()

By Milovan Savic, PhD Candidate, Swinburne University of Technology and Kath Albury, Professor of Media and Communication, Swinburne University of Technology. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.