The benefits – and pitfalls – of working in isolation

In Summary

- Analysis for The Conversation by Dr Agustin Chevez, Adjunct Research Fellow, Centre For Design Innovation, Swinburne University of Technology.

In October a researcher at the remote Bellingshausen Station in Antarctica allegedly stabbed a colleague. Some reports attributed the incident to the victim giving away the endings of books the attacker was reading.

Other reports identify the cabin fever effect as a possible contributing factor. During extended periods in isolation and confined conditions, such as at a station in Antarctica, people can become restless, bored and irritated.

These effects, however, are not limited to the small number of scientists living in cabin-like environments in remote locations. Isolation can just as easily affect people on the move, such as the drivers of the 3.5 million freight vehicles registered in Australia. Studies cite social isolation as a recurring theme and a cause of mental health problems and dysfunctional family relationships for truck drivers.

Interestingly, knowledge workers are also increasingly prone to suffering from isolation. This is because the ability to work “anywhere, anytime” has led to the development of new organisational structures that have increased the effects of isolation by increasing the social distance within a distributed workforce.

Depression, stress, lack of motivation and eventually burnout are all possible consequences of isolation. Other effects include experiencing fears of missing out on crucial events or decisions being made by others elsewhere – colloquially known as the feeling of out of sight, out of mind.

The impact of isolation in health has been compared to the reduction in lifespan similar to that caused by smoking 15 cigarettes a day. If the sit-to-stand desk was the response to the “sitting is the new smoking” motto, co-working is the response to isolation.

The growth of the gig economy brought concerns of increased likelihood of people working in isolation beyond that of teleworkers already discussed above. In this regard, the proliferation of co-working environments should not be surprising. To a large extent it’s due to their ability to provide a social environment for sole practitioners who would otherwise be working in isolation.

In pursuit of solitude

Isolation is an interpretation of one’s sense of aloneness. It is a feeling independent of the condition of being alone. While aloneness is the objective state of not having anyone around, isolation can be experienced in the middle of a crowd – if, for example, you have nothing in common with them, or do not share a common language.

Isolation is the negative side of aloneness, which leads to loneliness.

On the other hand, solitude is the positive manifestation of aloneness. An important factor in converting aloneness into solitude is that it is voluntary, instead of imposed. As such, artists, writers and scientists have described solitude as their most creative and productive state.

The differences between loneliness and solitude can be subtle. One study has identified that our understanding of these nuances develops with age.

Aloneness as a thinking tool

I have a particular interest in aloneness, both as an academic and architect. I specialise in the study of work and the environments that contain it. Specifically, I am interested in aloneness as a mechanism to increase the diversity of ideas.

This might seem at odds with the thinking of times when the value of collaborative work in Australia has been estimated at A$46 billion per year. However, the message of “the more, the merrier” when it comes to collaboration is increasingly being qualified and the downside of collaboration overload discussed.

Inspired by the development of diversity in species attributed to isolation (see iguanas at the Galapagos Islands), I walked alone from Melbourne to Sydney in the hope that I could incubate an idea for the duration of the 42-day journey. I was incubating the idea of a new sense of purpose in a post-artificially intelligent world.

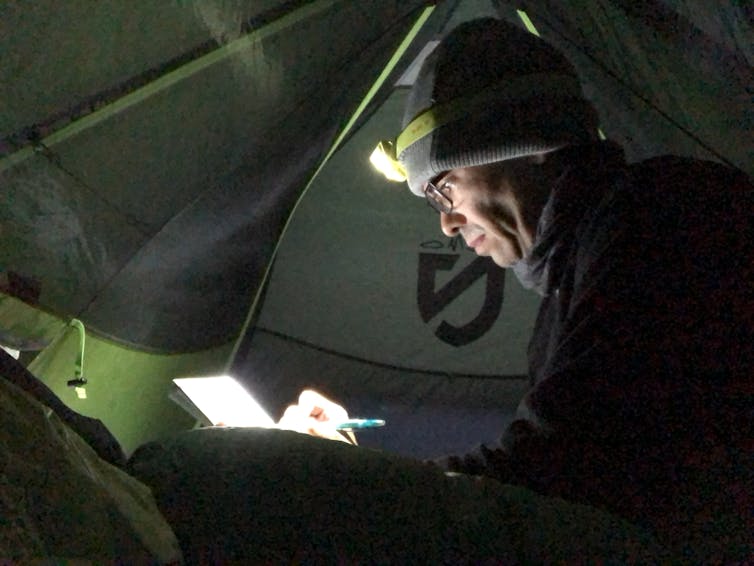

I carried two backpacks weighting up to 20kg, depending on the amount of food and water I needed, or if my tent got wet. I camped, or stayed in pubs, Airbnbs and roadside motels from a bygone era.

Camping between Melbourne and Sydney. Agustin Chevez, Author provided

Most people asked “why?” and what charity I was walking for (I wasn’t). What I learned is more complicated. But, yes, I did find that walking in solitude can be a great thinking tool. It is necessary, however, to be able to go past boredom – and that is not easy.

I mostly enjoyed my solitude, but I did experience loneliness during my trek. Interestingly, the literature suggests that isolation can also lead to lack of “social barometers”, making it difficult for people to determine how they should behave in work settings. I experienced a version of this as soon as I shared my first meal back in “civilisation” and realised how much I had relaxed my eating etiquette.

The nature of a specific job, like a scientist in Antarctica or a truck driver, might impose aloneness, or else it might be a side effect of mobile technologies or the emergence of the gig economy and other modern working styles. In such cases, the consequences of isolation must be managed.

At the same time, however, we should create opportunities for solitude in work settings, by the design of the space or of our jobs. In doing so, we might increase the diversity of ideas and ultimately our chances to innovate.![]()

Written by Agustin Chevez, Adjunct Research Fellow, Centre For Design Innovation, Swinburne University of Technology. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.