What consumers need from the ACCC inquiry into Google and Facebook

In Summary

- Analysis for The Conversation by Amanda Scardamaglia Senior Lecturer, Department Chair, Swinburne Law School, Swinburne University of Technology and Angela Daly, Vice Chancellor's Research Fellow, Queensland University of Technology

Yesterday the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) launched an inquiry into digital platforms including Google and Facebook.

Chairman of the ACCC Rod Sims said:

The ACCC will look closely at longer-term trends and the effect of technological change on competition in media and advertising.

We will also consider the impact of information asymmetry between digital platform providers and advertisers and consumers

The inquiry is overdue. To be useful, it should recognise that consumer protection law can play a larger role than it does currently in addressing platform power in the digital economy. Those leading it need to ensure its outcomes are truly beneficial for consumers, and not just the media companies and businesses using online advertising.

Read more: Confusion over Google’s paid services could land it in trouble, again

How Google presents information

To date, limited attention has been given to the issues faced by Australian consumers in internet markets, and particularly internet search.

Our research focuses on what consumers see and experience when they use Google.

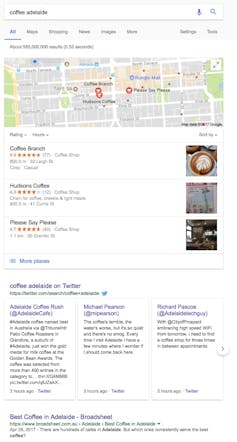

A search for ‘coffee adelaide’ produced the following results - but which are ads, and which are organic content? CLICK TO EXPAND AND VIEW

In the early days, Google’s search results page was essentially a combination of organic search results (those that result from Google’s algorithm that ranks according to relevance) and ads (a pay-per-click model of advertising). This provided for a relatively clean page with each of the two main elements delineated by labels and shading.

As Google has grown and its services evolved, Google’s search results page has become increasingly complex, with several competing elements. Many of these search results elements are derived from Google’s subsidiary “vertical search” services which provide users with a specific category of online content, such as Google Maps, Google News and Google Shopping.

Our research shows this creates confusion. We found that:

-

Australian consumers have a limited understanding about the operation and origin of different parts of the search results page

-

consumers were best able to understand and identify paid advertisements, as compared to results that were organic or linked to subsidiary services

-

there was particular confusion about the operation and origin of Google’s Shopping service, but also the origin of organic search results

-

confusion seems to be more pronounced among older users and those without higher education qualifications.

These findings point to a gap in consumers’ digital literacy about Google search that should be addressed by this ACCC inquiry.

Past ACCC focus on Google

In 2011, the ACCC brought proceedings against Google for breaches of the then Trade Practices Act 1974 (Commonwealth).

The ACCC alleged that by publishing or displaying several misleading sponsored links, Google was liable for misleading and deceptive conduct, as the maker of those advertisements (the claim against the advertiser was settled). The ACCC also claimed Google had engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct by failing to distinguish sufficiently between its organic search results and sponsored links.

The case went all the way to the High Court, who dismissed the case against Google. They found the evidence against Google never rose so high as to prove that Google personnel, as distinct from the advertisers, had chosen the relevant keywords, or otherwise created, endorsed, or adopted the sponsored links. As such, Google was not liable as the maker of misleading and deceptive advertising content.

Justice Nicholas in the Federal Court at trial also found against the ACCC’s allegation that Google had failed to distinguish its organic search results and sponsored links. He said reasonable members of the public would have understood sponsored links were advertisements that were different from Google’s organic search results.

As shown above, our research suggests otherwise. Despite its win against the ACCC in the High Court in 2013, Google should consider taking simple steps to label the different parts of its search results page more clearly, or risk legal action once more.

A guide for the future

In our recent submission to the Australian Consumer Law Review Issues Paper, we advocated for an evidence-based approach to all regulatory action under Australian consumer law.

We have also argued that agencies such as the ACCC should consider introducing “best-practice” guidelines for online search providers and comparison shopping services in relation to the use of labelling and disclaimers to clearly identify source and affiliation, in order to minimise consumer confusion.

Read more: Yes, your doctor might Google you

In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission issued similar guidelines about how these services should operate, and stated that failure to adequately distinguish between these different kinds of results may constitute a deceptive practice in violation of consumer protection laws. These guidelines provide a good starting point for regulatory agencies in Australia.

We also think further research is warranted that focuses on how different factors influence display of search results. We know this can vary depending on region, user preferences and settings, browsing history and devices used (PC, laptop, tablet or mobile phone).

We believe there is the potential for a more active role for consumer law in the digital ecosystem to address problems emanating from large and powerful platform providers such as Google than it previously has occupied. Perhaps this inquiry is the first step towards that.

However, it will be important for the ACCC to separate out the interests of consumers from the interests of businesses using Google to advertise, and media companies. Sometimes these interests converge, but not always. This can be seen in the recent European Commission investigation into Google’s alleged abuse of a dominant position in the search and advertising markets. These proceedings have resulted in an outcome which may benefit Google’s competitors more than consumers.

![]() The ACCC should be wary about producing the same outcome in its own inquiry, which is expected to produce a preliminary report in December 2018, and a final report in June 2019.

The ACCC should be wary about producing the same outcome in its own inquiry, which is expected to produce a preliminary report in December 2018, and a final report in June 2019.

Written by Amanda Scardamaglia, Senior Lecturer, Department Chair, Swinburne Law School, Swinburne University of Technology and Angela Daly, Vice Chancellor's Research Fellow, Queensland University of Technology. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.