Afternoon slump or the brain’s expectations at work?

In Summary

- The brain’s reward processing system fluctuates through the day, peaking in the morning and evening

- Reward pathways are partly driven by the circadian system or body clock

- Findings have implications for treatment of bipolar disorder and other conditions

The brain’s reward centre activates differently across the day, peaking in the morning and evening, according to new research from Swinburne’s Centre for Mental Health.

PhD candidate Jamie Byrne and her supervisor Professor Greg Murray say this shows that the brain's reward system is probably connected to the internal clock that primes 24-hour physiological and psychological processes.

They say the findings have significant implications for neuroscience research, which has typically ignored the time of day at which the brain is investigated.

The researchers hypothesised that the brain’s reward pathways would show predictable variation across the day because they are partly driven by the circadian system or body clock.

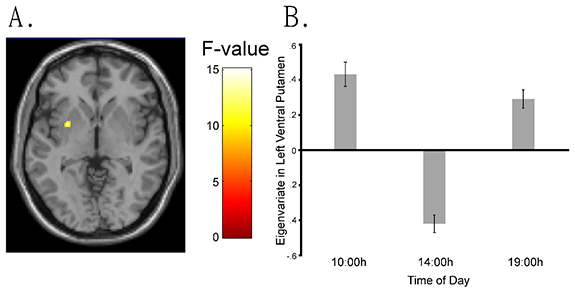

Sixteen healthy, right-handed men were given a gambling task across different times of day: 10am, 2pm, and 7pm. They were asked to guess the value of a card from a range of 1 to 9.

The subjects received a financial bonus for their best performance of the three times they completed the test.

Throughout the exercise, their brains were monitored by functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Activation of the left putamen is significantly decreased at 2pm, compared to 10am or 7pm. Neural activation might be higher in the left putamen in response to unexpected rewards (rewards that occur at 10am and 7pm) compared to rewards at expected times of day (2pm).

“We found that activations in the left putamen, the reward centre located at the base of the forebrain, were consistently lowest at the 2pm measurement compared to the start and end of the day,” Ms Byrne says.

This finding contrasts with previous research showing behavioural measures of reward activation peak around the early afternoon.

“Our best bet is that the brain is 'expecting' rewards at some times of day more than others, because it is adaptively primed by the body clock,” Ms Byrne says.

“The data suggest that the brain's reward centres might be primed to expect rewards in the early afternoon, and be 'surprised' when they appear at the start and end of the day.”

The findings encourage future research to determine how the different aspects of brain reward vary across the day, with potential implications for treatment of bipolar disorder and other conditions.

The research has been published in the Journal of Neuroscience.