More philanthropy means more risk-taking – and that’s good

In Summary

- Analysis for The Conversation by Krystian Seibert, Adjunct Industry Fellow, Swinburne University of Technology

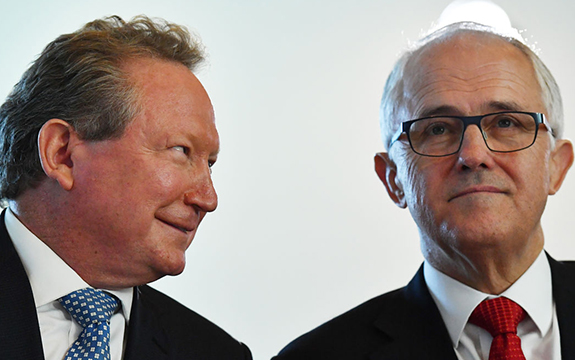

Monday’s announcement by mining magnate Andrew Forrest and his wife, Nicola, that they will commit A$400 million toward a range of causes was an important day for Australian philanthropy. ![]()

The size of the philanthropic commitment – Australia’s largest ever by living donors – certainly drew attention, as did the direction of the funds toward ambitious initiatives. There’s $75 million for a global drive to end modern slavery. Another $75 million will be directed to develop a new blueprint for child development in Australia and beyond.

The announcement again highlighted that philanthropy in Australia really is coming of age.

A shift toward ‘strategic’ philanthropy

Australia is seeing more, and larger, donations. But there’s also now a focus on more strategic philanthropy, which tries to tackle the root causes of complex problems through collaboration, research and advocacy. The Forrests’ efforts to end slavery and improve child development clearly fit into that category.

Philanthropy in Australia is still relatively small – especially when you compare it to the size of government and the economy.

The size of Australian philanthropy in perspective. Compiled using Australian government data

The size of Australian philanthropy in perspective. Compiled using Australian government data

But, as the philanthropic sector gets bigger, more people will start to question its influence and power. There was certainly an element of this in some of the social media and talkback radio comments responding to the Forrests’ announcement.

Paraphrasing some of the comments, some are uncomfortable with philanthropists using their money to influence social change. They ask why they should the shots – unlike elected governments, philanthropists are not democratically accountable.

This is a more common concern in the US, given the growing number of “mega” philanthropists there. This criticism overlooks the fact that philanthropic dollars can be used in a very different way to government dollars, precisely because they are not subject to the same sort of accountability.

Governments are often criticised as being slow, unresponsive, risk-averse, and unable to innovate. This is not an entirely fair criticism, because governments can and do take risks and innovate. However, there is also some truth to the claim. Governments can’t take the same risks as philanthropists – and that’s one reason why philanthropy is so important.

Some refer to philanthropy as risk capital for social change. This means philanthropy can be more nimble and responsive, and it can push boundaries and support innovation in areas which governments may be reluctant to tread.

While most would probably expect governments to try to innovate, few would necessarily expect or want them to push boundaries. But sometimes that’s exactly what you need, and what you can do when you’re not constrained by electoral cycles or the scrutiny of your political opponents.

Perhaps the best modern example of this is the role played by philanthropy to pave the way for the Iran nuclear deal struck in 2015. Since 2002, the US-based Rockefeller Brothers Fund provided US$4.3 million in funding to support the so-called “Track II” diplomacy with Iran.

This initiative brought together senior former government officials from both countries to engage in the kind of talks that could not happen through official diplomatic channels. Secret meetings, co-convened and chaired by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, were held in locations in Europe with the aim of building an understanding of the respective positions of the US and Iranian governments.

The participants routinely briefed officials back home regarding the discussions, helping grow each nation’s understanding of the other’s position.

Over time, many barriers were broken down. Eventually one of the key participants was made foreign minister in 2013 by the newly elected Iranian president, Hassan Rouhani. This helped jump-start the formal negotiations that led to the deal.

It’s not just about the money

The Forrests have bold ambitions for their philanthropy, perhaps inviting some cynics to be dismissive of their aims. Ending modern slavery is no easy task. But the Rockefeller Brothers Fund was also ambitious when it came to Iran, and the risk it took paid off.

Philanthropy doesn’t only bring money to the table. Philanthropists can also use their voices to advocate for change – something Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull praised the Forrests for in his remarks on Monday. Philanthropists can use their convening power to bring together communities, civil society organisations, experts, governments and others around issues.

While philanthropic bodies are not democratically accountable like governments are, that certainly does not mean they are not accountable at all. Australian philanthropy is very well regulated – and the activities of all foundations, including the Forrests’ Minderoo Foundation, are overseen by the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commmission.

To be effective, philanthropy relies on networks of stakeholders with whom it works - civil society organisations, subject matter experts, governments, and members of the community. These networks are also a source of accountability for philanthropy, and it must cultivate them in order to ensure it is regarded as legitimate.

Transparency is also a source of accountability. Recent research shows there is growing awareness among philanthropists about the importance of being open and transparent about what they do.

Ultimately, more philanthropy means more risk-taking to find new ways to tackle the challenges confronting Australia and the world. It’s important that the value of this risk-taking is recognised, and that we welcome philanthropists like the Forrests being bold with what they do, and open about how and why they’re doing it.

Written by Krystian Seibert, Adjunct Industry Fellow, Centre for Social Impact, Swinburne University of Technology. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.