Fred Rose: communist, scientist, lover, spy

In Summary

Klaus Neumann, Swinburne University of Technology

This article first appeared in Inside Story.

Review

Red Professor: The Cold War Life of Fred Rose

By Peter Monteath and Valerie Munt | Wakefield Press | $39.95

“When we began our research there was not so much as a Wikipedia article on Fred Rose, at least not on our Fred Rose,” write Peter Monteath and Valerie Munt in their introduction to Red Professor. There still isn’t.

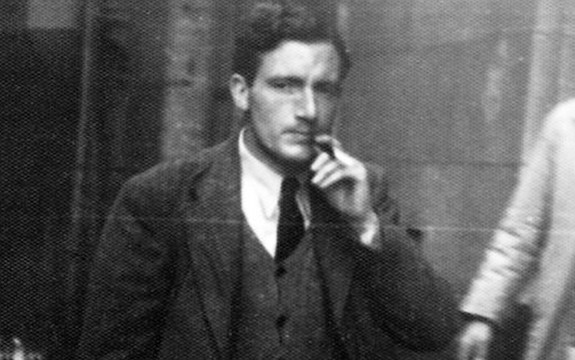

A Wikipedia entry would presumably be titled “Frederick Rose (anthropologist).” It would provide the key dates of Rose’s life (born 22 March 1915, died 14 January 1991). It would mention that he grew up in London, studied at Cambridge, left England in 1937 to become an anthropologist in Australia, and worked as a government meteorologist from 1937 to 1946, and then as a Canberra-based public service research officer for the next seven years.

A Wikipedia entry might tell us that Rose did ethnographic research in northern and central Australia, some of it while working for the Bureau of Meteorology, and that he published several books about Aboriginal culture. We might also learn that he was a committed communist, that he was implicated in the spy scandal that followed the defection of Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov in 1954, and that he then left the public service, worked as a wharfie for a couple of years, and in 1956 emigrated to the German Democratic Republic, where he became a professor of social anthropology.

I first heard of Fred Rose around thirty years ago, soon after I embarked on a PhD in the Department of Pacific and Southeast History at the Australian National University. A young East German anthropologist wanted to come to Australia to do research, one of my supervisors told me. Could I tell the department whether, in my opinion, she was a bona fide scholar? She had two articles in an East German journal of anthropology and archaeology to her name, one of them about bark paintings and the other about the nineteenth-century Tasmanian Aboriginal woman Truganini.

The applicant came with recommendations from Dymphna Clark, the wife of the university’s larger-than-life emeritus professor of history. It was Rose who had elicited Clark’s support for the young East German, but it also seemed to be Rose who was responsible for the fact that the request was being dealt with by Pacific historians rather than by anthropologists. Rose had co-authored her academic papers, but the correspondence with my university suggested that he was perhaps more than just a mentor. The matter was evidently delicate.

I was intrigued. Why would the East German authorities allow Rose’s young colleague to visit Australia – not for a brief visit to attend a conference, but for several months? In the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev had just been elected general secretary of the Communist Party. In Poland, martial law (imposed after the conflict between the state and Solidarity) had been lifted in 1983, and the communist party seemed willing to tolerate a gradual liberalisation of Polish society. In the German Democratic Republic, however, Erich Honecker and the Socialist Unity Party governed with an iron fist and rejected all suggestions for reform. For many East Germans, reform would have been synonymous with the ability to travel to Western countries, but apart from pensioners, who were allowed to visit relatives in West Germany, only a select few were granted exit visas. They included the country’s top athletes, artists and scientists – provided, of course, they could be trusted to return. Rose’s protégé didn’t fit any of these categories.

I seem to recall that a visiting fellowship was offered to the young woman despite rather than because of the politics involved. The university’s Pacific historians believed that they were doing a good deed by allowing an anthropologist writing about Australia and the region to gain some first-hand knowledge of the peoples she purported to study. I still remember clearly the day we broke the news to her by phone. After one of the department’s senior researchers had failed to make himself understood – speaking very slowly but with the strongest Australian accent – it fell to me to tell her that, yes, the ANU would accommodate her, and that we were hoping that her government would allow her to come.

I was in Papua New Guinea doing fieldwork during the time she spent in Canberra, and didn’t meet her until soon after the Berlin wall came down. I was visiting her home town of Leipzig to see for myself what the Wende – the East German transition to democracy – was all about. I was impressed by the civil rights activists who had occupied the Leipzig office of the Stasi secret police and who told me about its repressive practices and its paranoia, and amazed when I learnt about the extent to which the Stasi could rely on a network of informers. But I was also taken aback by the fact that everyone else I talked to identified as a victim of communism, and was eager for capitalism’s supposed material benefits.

In Red Professor, the young East German anthropologist is called “Anna Wittmann.” I’m not sure why the authors have chosen to conceal her identity, but I’ll follow their lead. “Wittmann” isn’t the only person from Rose’s life given a pseudonym: a “Heidi Manne” plays a marginal role as a junior Australian diplomat; she went on “to become UNHCR Assistant High Commissioner,” so her real name is not hard to guess.

Monteath and Munt confirm what those dealing with Wittmann’s application to visit ANU suspected: that she was Rose’s lover. He had met her when they were both living in Leipzig and working for the local Museum of Anthropology. They possibly had a child together.

Fred Rose had an “innate ability to compartmentalise his life,” according to Monteath and Munt. He was a passionate campaigner for Aboriginal rights yet a dispassionate empiricist when writing about Aboriginal cultures. He was a conscientious Canberra public servant and an active member of the Communist Party. He was caught up in relationships with women (frequently with more than one at a time) but kept his private life separate from his politics.

The compartment that receives particular attention in Red Professor is Rose’s interaction with intelligence agencies, both in Australia and in East Germany. Did he spy for the Soviet Union while working as a public servant in Australia? The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, or ASIO, clearly thought so, but the evidence is inconclusive. He was most likely the man codenamed “Professor” in Soviet cables decrypted by the United States during its Venona program. But the Petrovs had never met him and were not able to implicate him, and despite a lengthy and detailed investigation he was not charged with betraying government secrets.

The accusations levelled against him in Australia eventually precipitated Rose’s move to East Germany. They also prompted him to identify as a victim and to exaggerate the importance ASIO assigned to him. In 1954 and 1955, his role was investigated by the royal commission set up by the Menzies government in response to revelations about a Soviet spy network in Australia. The commission “profoundly affected Rose’s life,” Monteath and Munt write. “It left psychological scars that never fully healed… Rose found it increasingly difficult to clear his mind of the possibility that he was being watched.”

Rose’s paranoia was matched by that of Australia’s spymaster, ASIO director-general Charles Spry. Spry was forever suspicious, and often his suspicions were unfounded. Somebody like Rose, who made no secret of his allegiance to the communist cause, confirmed Spry’s bifurcated view of the world. In fact, as Monteath and Munt observe, “It is tempting to view [Spry] as an inverted image of Fred Rose.”

While Rose’s involvement with Soviet intelligence was never proven, there is little doubt about the unsavoury role he would play as an informer for the East German state security agency Stasi, reporting on his colleagues, his students, his wife and his son Kim. In Rose’s view, it was all for a good cause. I wonder how much his unwavering commitment was influenced by the treatment he received, or thought he received, at the hands of a fiercely anti-communist Australian government.

Perhaps we could better understand Rose’s role as a Stasi informer, and his identity as a communist, if we compared his life in East Germany with those of three of his contemporaries. The first is Walter Kaufmann, a German Jew who arrived in Sydney in 1940 on the infamous Dunera. Like Rose, he became a communist in Australia and, again like Rose, he left Australia in the 1950s to live in the German Democratic Republic. Kaufmann seems never to have fully assimilated to life in the GDR; perhaps his coming-of-age in Australia proved as formative as his childhood in Germany. Then there was John Peet, an English journalist who moved to East Germany in 1950, became a propagandist for the communist regime and remained a communist until he died in 1988, but who was nevertheless able to be critical (and, to the best of my knowledge, never offered his services to the Stasi). And finally, there was Wolfgang Steinitz, the subject of an excellent biography by the German historian Annette Leo. Like Rose, he was a prominent anthropologist in East Germany who remained loyal to his communist ideals; unlike Rose, he grappled with the contradictions between these ideals and the socialist reality.

Fred Rose preceded his young colleague to Canberra in 1986, and I was introduced to him one day in the Coombs Building’s tea room. He seemed to blend in with the overwhelmingly white, male, middle-aged, cardigan-wearing crowd. I would have been too shy to engage somebody who was evidently holding court in conversation. But I also told myself that I had little interest in him. Having checked out his anthropological writings when I’d been asked to report on his protégé’s scholarship, I had found his observations about Aboriginal kinship on Groote Eylandt too dry and his ideas about anthropology antiquated.

Now I much regret that I didn’t get to know Fred Rose when I had the opportunity – if only because I am now curious about his status as an anthropologist. Was he “certainly a poor anthropologist, inadequately trained (in spite of his Cambridge degree) and intellectually arrested,” as the ANU’s inaugural chair in anthropology, Fred Nadel, thought in 1950? Or did he do “highly original work” and make contributions to kinship studies that “rate comparison” with the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss, as another Australian-based anthropologist, Kenneth Maddock, wrote after his death?

In one respect at least, he appeared to be ahead of his time. In a book about Aboriginal Australia published in German in 1969, he wrote about the impact of European settlement on Aboriginal societies:

How have their views of the environment changed…? At the same time the interesting question arises: How have European settlers’ perceptions of Aborigines changed during the same period? The relations between Aborigines and white settlers have always been marked by the mutual influence they had on one another.

In the 1960s, most Australian anthropologists would have been baffled by Rose’s idea of exploring the influence Aboriginal people had on settler-colonial society.

Neither Rose’s reputation as an anthropologist nor his putative role as a spy for the Soviets would have warranted a full-length biography. Both in his professional life, and as a true believer in communism and the party that claimed to be best positioned to work towards it, Rose comes across as obsessive, conservative and somewhat dour – although I concede that my reading of Red Professor may have been shaped by memories of my fleeting encounter three decades earlier. It’s interesting that he emigrated to a communist country, but his role as a Westerner in Walter Ulbricht’s and Erich Honecker’s East Germany seems surprisingly unremarkable, particularly compared with the activities of his fellow countryman, John Peet.

That leaves one compartment of Rose’s life: his relationships with women. Monteath and Munt treat this aspect of his biography with kid gloves – or maybe they think it incidental to Rose’s persona as a researcher and writer, as a communist and as a spy. Often we have to rely on inferences, and very often we are invited to rely on Rose’s version of events. Occasionally comments about Rose’s sex life smack of a false sense of camaraderie (“Put colloquially, Rose was a dog inclined to stray from the porch”). Potentially, however, the contradictions between the personal and the political are what make Rose a fascinating biographical subject.

Take his early years in Australia, for example, when he was engaged to Edith Linde, a German woman he had met in England who would later join him in Darwin and eventually become his wife. According to Monteath and Munt (who rely on Rose’s draft memoirs), while working as a government meteorologist in Darwin, Rose became concerned that his ethnographic moonlighting could be interpreted as a cover for having sex with Aboriginal women. To “forestall any such accusations… he resolved to establish a relationship with a white woman” (who turns out to be the married manager of a local hotel, and “a keen golfer”).

Edith too was a communist. She would precede her husband to East Germany, where she too willingly worked for the Stasi and provided information about her husband, among others. Throughout most of Fred and Edith’s relationship, her allocated role was as mother of their children; other women in Rose’s life were lovers, former lovers and potential lovers.

There is nothing dour about Fred Rose’s relations with women. With his keen interest in the opposite sex, Rose presented himself as a likeable and lively character. Political scientist Coral Bell, who worked in the Department of External Affairs in Canberra in the second half of the 1940s, remembered Rose as “a great charmer who always seemed to be at everyone’s parties.”

And despite all his compartmentalising, his private life and his work as an anthropologist sometimes seemed to intersect. As he grew older, he was often more than twice the age of his lovers. At the same time, the aspects of Aboriginal society that seemed to hold particular interest for him were polygyny and gerontocracy, which he considered to be “reciprocally dependent.”

Biographers have to make do with the sources at their disposal. In this case, many of the sources were written by Rose himself. We know nothing about the Darwin woman whose role it was to provide proof that Rose’s relations with Indigenous women were purely professional. We know little about how Edith experienced the relationship with her husband. And, more’s the pity, Anna Wittmann’s side of the story is missing altogether.