Double 'peanut shell-shaped' feature of a galaxy discovered

In Summary

- Astronomers have discovered an unusual twin peanut shell-shaped structure in two nearby disc galaxies.

- The discovery may shed new light on the peanut-shaped bulge of our own Milky Way Galaxy.

Swinburne astronomers have discovered an unusually shaped structure in two nearby disc galaxies.

The distribution of stars bulging from the centre of these galaxies’ flattened discs resembles two peanut shells, with one neatly nested within the other.

“This is the first time such a phenomenon has been observed," says Bogdan Ciambur, the PhD student who led the investigation.

“We expect the galaxies’ surprising anatomy will provide us with a unique view into their pasts. Deciphering their history can tell us about transformations that galaxies like our own Milky Way might experience.”

New imaging software aids discovery

The Swinburne team recently developed new imaging software, making it possible to find the delicate features that led to this discovery.

Using data from the Hubble Space Telescope and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, the researchers realised that two of the galaxies they were studying – NGC 128 and NGC 2549 – were quite exceptional. They displayed a peanut shell configuration at two separate layers within the galaxies’ three-dimensional distribution of stars.

“Ironically, these peanut-shaped structures are far from peanut-sized,” says Swinburne Professor Alister Graham, co-author of the research. “They consist of billions of stars typically spanning 5-25 per cent of the length of the galaxies.”

Although the ‘bulges’ of both galaxies were already known to display a single peanut shell pattern, astronomers had never before observed the fainter second structure in any galaxy.

How does this bulge occur?

Astronomers believe peanut shaped bulges are linked to a bar-shaped distribution of stars observed across the centre of many rotating galaxy discs. Each of the two galaxies observed contain two such bars.

One way the peanut shaped structures may arise is when these bars of stars bend above and below the galaxy’s central disc of stars.

“The instability mechanism may be similar to water running through a garden hose,” says Mr Ciambur. “When the water pressure is low, the hose remains still – the stars stay on their usual orbits. But when the pressure is high the hose starts to bend – stellar orbits bend outside of the disc."

By directly comparing real galaxies with state-of-the-art simulations, the researchers hope to better understand how galaxies evolve.

“The discovery is exciting because it will enable us to more fully test the growth of bars over time, including their lengths, rotation speeds, and periods of instability,” Mr Ciambur says.

The study may also shed new light on the peanut-shaped bulge of our Milky Way Galaxy, which some astronomers suspect contains two stellar bars.

“Thankfully we can observe it from afar as we are too distant to get caught up in the dizzying orbits that lead to these interesting peanut shell patterns,” says Professor Graham.

This research has been published by the Oxford University Press in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

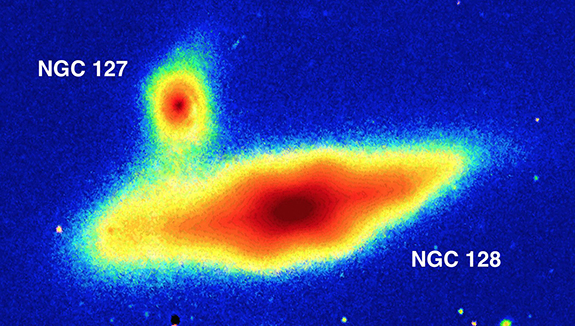

Left: The galaxy NGC 128 is viewed with its disc in an edge-on orientation in this SDSS false-colour image. A peanut shell-shaped bulge can be seen around the thin disc. Its inner peanut shell is five times smaller. Image credit: SDSS, B.Ciambur.

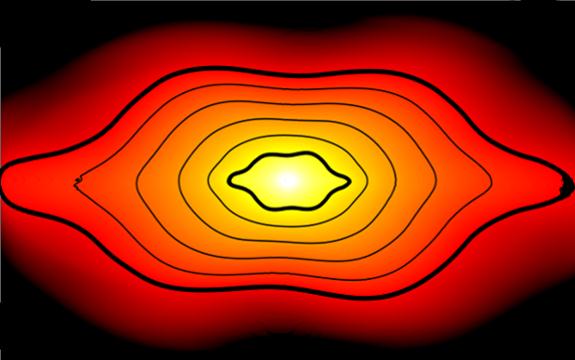

Right: A zoom-in with the Hubble Space Telescope into the core of NGC 2549 reveals the inner peanut shell shaped structure in this galaxy. Its outer peanut shell is three times bigger. Image credit: NASA, ESA, B.Ciambur.