Refuting the censorship argument is child's play

In Summary

- Analysis for The Conversation by Professor Dan Hunter, Dean of Law, Swinburne University of Technology

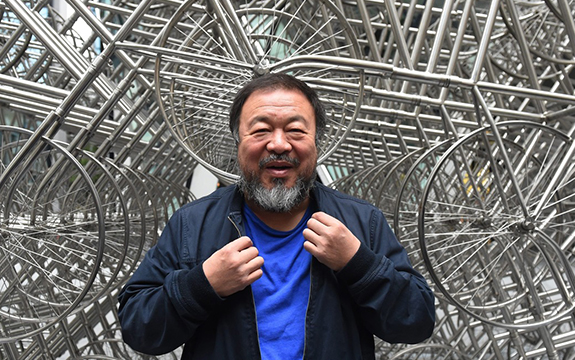

Unless you’ve been playing with your building blocks for the past couple of weeks you’ll know the internet is abuzz with news that Lego refused to sell Chinese contemporary artist Ai Weiwei a large number of its toy bricks for his latest art installation, to be unveiled on December 11 at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne.

When the news first broke, commentators suggested that this was connected to the announcement that Lego had recently signed a deal to open its first theme park in China.

Ai Weiwei is a remarkable artist and provocateur, known for his brilliant attacks on the Chinese government via his art. Despite Lego’s protestation that it’s just avoiding controversy, Weiwei, in concert with numerous media outlets, has claimed that Lego is engaging in heavy-handed censorship.

A standard trope suggests that this is a war between art and commerce.

There are so many things wrong with those arguments it’s hard to know where to begin responding. The main thing to note is that Lego’s actions aren’t censorship – they don’t even resemble censorship. It’s not like Weiwei is now unable to buy Lego bricks to express his artistic vision.

If he wants, he can get his assistants to wander down to the local toy store and buy any number of sets; and if that’s too much like hard work he can order from the numerous wholesale Lego merchants that populate eBay, or any one of myriad online wholesalers and retailers.

Lego can’t put a worldwide ban on the sale of bricks to Weiwei, and wouldn’t do so even if it could. Instead, the company has merely said that it doesn’t get involved in political statements using the bricks, commenting last month that:

as a company dedicated to delivering creative play experiences to children, we refrain – on a global level – from engaging in or endorsing the use of LEGO bricks in projects that carry a political agenda. Individuals may obtain LEGO bricks in other ways to create their LEGO projects if they so desire, but in cases where we receive requests for donations or support for projects – such as the possibility of purchasing LEGO bricks in very large quantities – and we are aware that there is a political context, we uphold our corporate policy and decline the request to access LEGO bricks directly.

This would be a smart and reasonable approach for a company such as Lego, no matter what had happened to it in the past. But Lego has a history of difficulties with its users; and so its concern is more understandable.

Lego has created a general-purpose technology that can be used to make all sorts of things the company has no control over. And it has confronted a range of problems as a result, usually from so-called “Adult Fans of Lego” who don’t play with Lego in the same way as kids. These users create models of guns and weapons that can be used to take out an eye, they produce YouTube videos of the battle on the Star Wars iceplanet of Hoth, or create models of the Serenity spaceship from Firefly, without approval from the film studios that own the intellectual property rights. Much to the consternation of the company.

Generally Lego executives have realised they’re on safest ground when they don’t take a position on the things that their users create; otherwise they will be seen as endorsing them.

A car parked next to the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin serves as a donation point for Lego bricks with which Ai Weiwei will recreate the portraits of prominent civil rights activists. Image credit: Sophia Kembowski, EPA.

So no wonder Lego doesn’t want to sell Weiwei bricks. But it’s worse than that. During the mid-1990s, Lego was approached by Polish artist named Zbigniew Libera for a donation of bricks, which the company happily agreed to. Using these bricks, Libera created an art installation of a series of fictitious Lego kits called Konzentrationslager, depicting scenes from Nazi concentration camps.

One set depicted skeletal prisoners behind barbed wire fences – Libera used skeleton minifigs from the Castle theme to depict the prisoners – while another shows a minifig being hanged on a gallows.

A third set shows skeletons being dragged into a crematorium blockhouse under the watchful eye of a black-clad guard, with the massive crematorium chimneys, all-too-familiar from Holocaust documentaries, towering above the roofline.

The use of the bricks for this installation caused the company a bit of heartburn; but the genuinely troubling aspect of the installation was that Libera created sets that featured the iconic LEGO logo in the top left of the box, so that the installation looks for all the world as though the company was crass enough to produce a commercial product from one of the worst examples of human suffering the world has ever witnessed.

The Ai Weiwei vs Lego case is an example of unfortunate corporate public relations, and the difficult intersection of a shameless artist-provocateur, a politically sensitive company, and the world’s largest police state. Weiwei last month came out with a position statement, decrying the company’s approach:

I think it’s funny to have a toy company that makes plastic pieces telling people what is political and what is not. I think it’s dangerous to have our future designed by corporate companies. They are not selling toys but selling ideas – telling people what to love and what to hate.

Perhaps Weiwei is just being naïve, or disingenuous, but I doubt it. I think he’s milking this for all it’s worth.

I for one won’t be donating my old Lego bricks to him, through the sun roof of his car.

![]() Written by Dan Hunter, Dean, Swinburne Law School, Swinburne University of Technology. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Written by Dan Hunter, Dean, Swinburne Law School, Swinburne University of Technology. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.