Swinburne's MEG is helping epilepsy patients

In Summary

Australian researchers have been able to pinpoint abnormal brain regions responsible for epilepsy, offering promise for improved surgical treatment.

In the collaboration between Swinburne University of Technology and St Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne, patients suffering from epilepsy have undergone Magnetoencephalography (MEG) scans to help with their diagnosis.

According to Professor David Liley from Swinburne’s Brain and Psychological Sciences Centre, 10,000 -12,000 new cases of epilepsy are diagnosed each year in Australia. Forty per cent are categorised as focal, suggesting epilepsy is arising from a certain area of the brain.

“At the moment surgical treatment for focal epilepsy is a very time consuming process. Often, it requires many kinds of different imaging tests,” Professor Liley said.

“Typically, to see which area of the brain is affected a surgeon needs to implant a number of temporary electrodes directly onto the patient’s brain, which can be costly, time-consuming and presents risk of further complications.

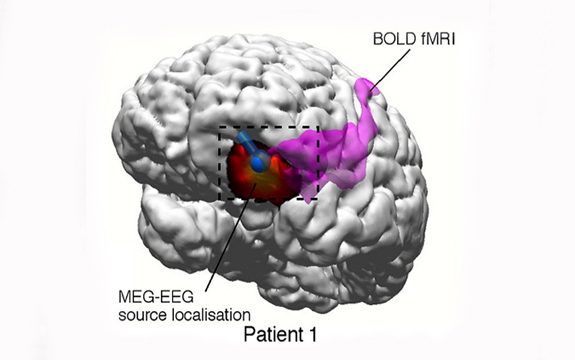

“MEG is a different and better way of doing this. The advantage of using MEG is that it measures the incredibly weak magnetic fields produced by the active brain, but is completely non-invasive.

“You can use MEG to see the abnormal activity in epilepsy without having to put electrodes directly on the brain. Planning for surgery can potentially be performed much more efficiently and cost effectively than existing approaches, which significantly improves the results of surgery.”

It is hoped the preliminary results from this work will help define the situations in which non-invasive MEG scanning can be used.

So far over fifty patients with epilepsy have undergone MEG scans in Melbourne. Stewart Duguid is one of them.

Now 24 years old, Mr Duguid has been suffering from epilepsy since he was 13. His first seizure began early one school morning when his mother found him on the floor convulsing uncontrollably.

Mr Duguid has had seizures every few weeks for the past 11 years, despite being prescribed many potent anti-epilepsy drugs.

In Mr Duguid’s case MEG was instrumental in accurately identifying the abnormal brain region responsible for his seizures so he could undergo the necessary surgical treatment for his epilepsy. After six months of treatment Stuart now lives seizure-free.

The MEG is part of Swinburne’s brain imaging facility, which is the only one its kind in the Southern Hemisphere.

To learn more about the unique capabilities of MEG and how it can be used in basic and clinical research and clinical decision-making, register for Swinburne’s Brain Imaging Symposium: http://www.swinburne.edu.au/research/our-research/brain-imaging-symposium/