What designers can learn from Aboriginal possum skin cloaks

In Summary

- Analysis for The Conversation by Myles Russell Cook, Lecturer, Design Anthropology and Indigenous Studies, Swinburne University of Technology

What is on the paper map is a representation of what was in the retinal representation of the man who made the map.

– Gregory Bateson

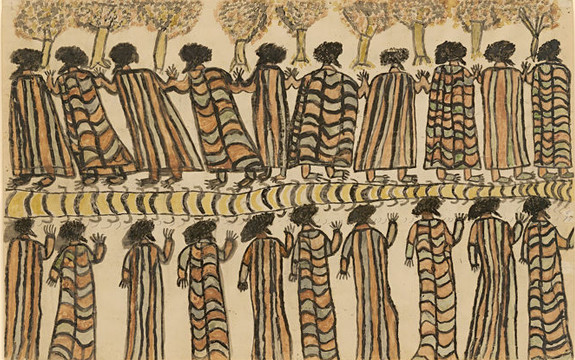

Contemporary clothing design draws on many traditions, appropriating and reworking what has gone before and learning from the past. Australian Aboriginal dress is rarely cited as a key inspiration – and, in that, I think many designers are missing an opportunity.

19th-century images of Aboriginal people from south-eastern Australia frequently feature subjects wearing possum skin cloaks.

More often than not the photographs show the fur side of the cloak, the part that was traditionally worn next to the skin for warmth and protection. The inner, worked skin – not shown in the pictures – was decorated with important images, stories and narratives.

Portrait of unidentified Aboriginal woman wearing a possum skin cloak, carrying a child on her back, South Australia, ca. 1870s. Image credit: National Library of Australia.

Possum skin cloaks typically comprise several possum pelts sewn together with kangaroo sinew. One side of the cloak is entirely furred, while the other is fleece. The decorations are typically made with hot-wire and pokerwork, and designs are burned into the hide.

Historically, possum skin cloaks were ubiquitous throughout south-eastern Australia. They were highly collectible by settler Australians and were easily – and forcibly – replaced by much inferior woven blankets.

By the mid-20th century a little over a dozen had survived, preserved in museums.

Koori artists Vicki Couzens, Lee Darroch, Maree Clarke and Treahna Hamm began a movement of reclaiming the practice of possum skin cloak-making as a contemporary design practice in 1999.

This has resulted in new cloaks being made for the first time in more than 150 years. (As possums are protected in Australia, pelts are imported from New Zealand, where possums are a pest.)

A number of cloaks were made for the 2006 Commonwealth Games opening ceremony; they also appeared on the shoulders of elders during the 2008 federal government’s apology to the stolen generations.

A living entity

Aboriginal people are popularly described as having been nomadic – a loaded term often used as a shorthand to mean they “wandered” and did not “work” the land – an inaccurate characterisation that has shades of the terra nullius doctrine.

The annual movements of Aboriginal people were carefully planned, taking into account seasonal abundances and shortages, water resources and access to prey animals. And the material culture of such mobile people needed to be developed accordingly – all objects needed to be portable and serve multiple purposes.

Possum skin rugs were an example of this. A rug might function as a cloak; it might fasten a baby to their mother; it might hold food collected and brought back to the camp for distribution. The internal markings and designs communicated the wearer’s story and functioned as narrative of country.

That story was typically place-related but was often also representative of an individual’s distinctiveness, heritage, kinfolk and relationship to the ancestors.

A possum skin cloak, sewn in a traditional way, but using skins from New Zealand possums. Image credit: Rhondda.

Traditionally a child would be given a pelt at birth by their skin clan and each year would attain another. The forms these cloaks took would often be varied, but there was a consistency in their relationship to the maker. Each individual would work to make their own cloak; there was no single cloak maker in any given community.

Making a possum skin cloak is an act of storytelling and map-making. In his (very short) short story On Exactitude in Science (1946) Jorge Luis Borges imagines the perfect map as being at a ration of 1:1:

… In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province.

But following generations, in the story:

saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winter.

Borges' point was that a map’s usability and its accuracy are directly opposed. But that’s not the case for possum skin cloaks: the map is always usable and always accurate, because the very thing being mapped is identity of the wearer.

With a a growing focus on sustainability, more and more designers are looking to create and design living things, where both the object and the meaning of the object change over time.

In classic design there’s an effort to de-link the designer and client, to distance an object from the story of its maker. Possum skin cloaks grow as the wearer grows; their meaning expands as their maker ages.

The question we should ask ourselves as designers is what can we learn from these practices of Indigenous material culture and how can we adopt similar methods, while remaining careful not to appropriate.

Written by Myles Russell Cook, Swinburne University of Technology. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.