Women losing trust in political leaders shows new Swinburne research

The Australian Leadership Index results show women are more likely to negatively view unethical behaviours by leaders, which in turn degrades public trust.

In summary

- The Swinburne Australian Leadership Index shows women’s perception of federal leaders took a steep dive from the end of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021

- During this period a string of political scandals were reported by the mainstream media

- The noticeable drop in women’s faith in the federal government warrants immediate attention, say Swinburne researchers

A string of shocking incidences from Parliament House has cast a light on its toxic culture, including allegations of ongoing sexual harassment, assault, and rape. From the Brittany Higgins case, to the March 4 Justice, and Scott Morrison’s startling reflection that the march was a ‘triumph’ in that it was ‘not met with bullets’; it is no wonder Australians, and women particularly, are feeling distressed and fed up.

Women are losing trust in our leaders

Mainstream media has commented on women’s deepening sense of anger and sadness, manifesting as distrust in federal government during the current political crisis. A recent poll found that about 68% of Australian women (and 62% of men) agreed with the statement: “The government has been more interested in protecting itself than the interests of those who have been assaulted.” Swinburne’s Australian Leadership Index (ALI) provides further evidence of the declining levels of public trust in the federal government.

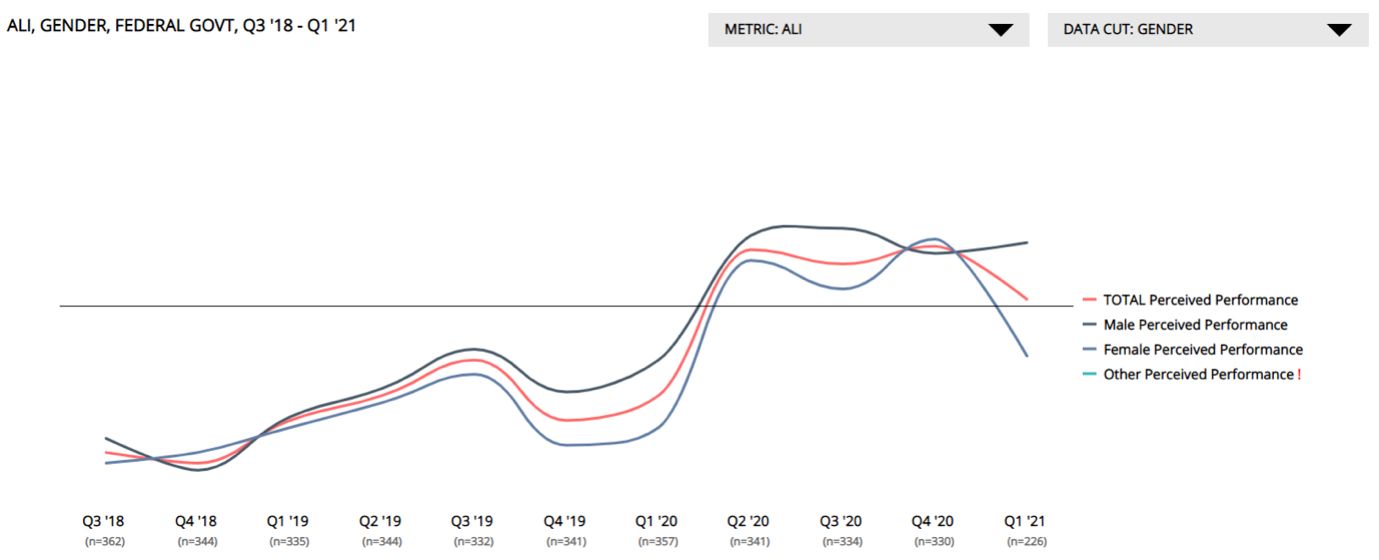

Figure 1: Public perceptions of federal government leadership from 2018-2021, by gender

As seen in Figure 1, women’s (but not men’s) perceptions of federal leaders took a steep dive from the end of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021 – the period in which a string of scandals were reported by the mainstream media. The noticeable drop in women’s faith in the federal government is alarming and warrants immediate attention to address the needs of the people, which is arguably one of the fundamental responsibilities of leaders and for the greater good of the country.

A need for ethical leadership in parliament

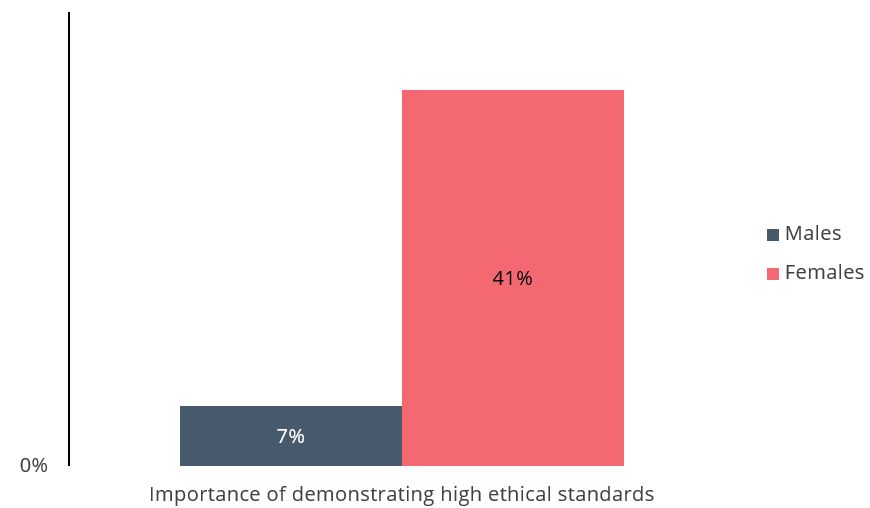

A closer look at the data showcases the importance of some drivers of the public’s assessments of leadership for the greater good. As seen in Figure 2, demonstrating high ethical standards is fundamental to women’s perceptions of federal leadership. Thus, women are more likely to negatively view unethical behaviours by leaders, which in turn degrades public trust.

Figure 2: Importance of federal government leadership demonstrating high ethical standards, by gender

The recent trend for Australian women is the importance of ethical conduct. Any effective changes to policy should be data driven and should target falling ethical standards. Strategies need to be transparent and authentic; vague statements and false promises will do nothing to restore dropping levels of public trust.

Restoring women’s faith and trust in federal leaders

The current problems with parliamentary culture will not be a simple fix, but there are promising long-term initiatives that could begin to be implemented now – ones that are well supported by existing research in ethical leadership and diversity management.

1. Perpetrators need to be held accountable: Violations that are tolerated become the norm.

Insights from social psychology have shown that when leaders appear to ignore or tolerate unethical behaviours, people within the social group, members of Parliament in this case, will begin to question the importance of existing moral norms and may engage in continued and progressively more serious violations, further eroding ethical standards (e.g. Bandura, 1963; Moore et al., 2019). Now is not the time to play politics, to avoid taking a stand by hiding behind vague statements. A clear signal is needed to show these acts will not be tolerated. Women in Australia need to see that their Prime Minister is going to act to disrupt the current toxic culture in order for public trust to be restored.

2. Critical mass of women in politics: It takes more than a token woman (or a few token women) to incite changes to policy or workplace culture.

One of the most immediate solutions is appointing more women into high level positions, a strategy that the Morrison government seems to be trying in the recently announced ‘cabinet shuffle’. It is worth noting that there are still some concerns about the backlash that strategically appointed women might face (Krook, 2015), including being seen as being unfairly appointed over more qualified others just because of their sex (e.g., Gillespie & Ryan, 2012; Leslie et al., 2014). However, this reshuffle is likely a step in the right direction for restoring trust to female constituents. Continued support for newly appointed cabinet members will be vital in the upcoming months.

3. Increased transparency: The role of independent reviews and committees

When trust in an institution is low, one way to ease the public’s concerns is by increasing the transparency of decisions, actions, and strategies for addressing problematic behaviour. The independent review into parliamentary workplaces by Sex Discrimination Commissioner, Kate Jenkins, is a great first step. Additionally, the federal government should consider appointing an independent committee to investigate and implement a series of evidence-based interventions aimed at restoring ethical standards in the workplace. The outcomes of this process could then be disseminated to all Australian workplaces, as a further display of the transparency of initiatives and as a way for all organisations to implement solid policies around workplace behaviour.

The Swinburne Australian Leadership Index is the largest ever ongoing research study of leadership in Australia.

-

Media Enquiries

Related articles

-

- Politics

What does the ‘common good’ actually mean? Our research found common ground across the political divide

Some topics are hard to define. They are nebulous; their meanings are elusive. Topics relating to morality fit this description. So do those that are subjective, meaning different things to different people in different contexts. In our recently published paper, we targeted the nebulous concept of the “common good”.

Tuesday 23 January 2024 -

- Technology

- Business

Swinburne's Venture Cup unveils pioneering startups as entrepreneurs take centre stage

Swinburne University’s annual Venture Cup pitch night shines a spotlight on remarkable startups by students, staff and alumni.

Thursday 11 January 2024 -

- Business

Is linking time in the office to career success the best way to get us back to work?

In what some employees consider an aggressive move by their bosses to get them back where they can be seen, some companies are now linking office attendance to pay, bonuses and even promotions.

Monday 22 January 2024 -

- Business

6 questions you should be ready to answer to smash that job interview

With the new year underway employers are beginning to resume normal business activities and restart their hiring process. Similarly, many school and university graduates are beginning their job search after a well-earned break.

Wednesday 17 January 2024 -

- Student News

Swinburne helps deepen multi-disciplinary understanding

Swinburne recently hosted nine Indonesian students as part of the prestigious Indonesian International Student Mobility Awards, Vocational Edition (IISMAVO).

Thursday 07 December 2023